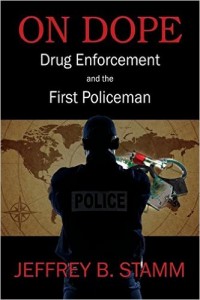

Jeffrey B. Stamm, a highly-decorated DEA agent for 31 years, served domestic and overseas assignments in South America and Central Asia. He rose from undercover agent to a member of DEA’s Senior Executive Service. In December 2015 he retired from the DEA to take a job as executive director of the Midwest High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area (HIDTA) based in Kansas City, Mo. The following is an excerpt from his new book: On Dope: Drug Enforcement and The First Policeman

INTRODUCTION

Civilizations die from suicide, not murder. –Arnold Toynbee

We are in grave danger of losing the debate against illegal drugs—dope—and, in the process, our very society. Not because of the inherent correctness of the arguments and opinions of those who advocate drug legalization or decriminalization, but due to the near-complete lack of an informed and engaged citizenry pushing back against the demagogues, apologists, and appeasers who peddle, with increasing success, only dangerous myths and false metaphors.

Their reckless and illegitimate accusations that the current drug control paradigm has not only “failed” but that it is patently “racist” and “oppressive” have served to bully and confuse a sleepwalking population too timid and self-absorbed to argue. In our attempt to be tolerant, sensitive and compassionate, we, instead, exhibit a stultifying weakness in the face of a zealous and committed pro-dope cabal intent on changing the landscape and the laws. Allowing them to succeed will produce catastrophic social and cultural consequences that will require generations, or longer, from which to recover.

Against an unceasing and withering torrent of criticisms against our current legal and political drug-control framework, we seem to have succumbed to the deceptions and propaganda of misguided “experts” who tout “new,” “daring” and “brilliantly innovative” policies in the face of our current “failures.” Through what has become something of a forced compulsion to nonjudgmentalism and pervasive compassion, we are increasingly surrendering to the false hopes of both the utopian liberals and fundamentalist libertarians who preach that “drug prohibition does more harm than good” and, further, that drug use “affects no one but the user himself.” Such views are not only utterly wrong, but destructive and fundamentally incompatible with a free and democratic society. Besides, there is no situation that cannot be made even worse through wrong and foolish policies.

It has been said that you don’t have to be a soldier to understand war, but it sure can help.[2] So, too, is this true in the arena of drug enforcement. Professor James Inciardi has argued that, at least every now and then, those who have the most to say about drug affairs ought to leave their “safe, secure and existentially antiseptic confines” and visit the mean and despairing streets to understand the scope and solemnity of the problem.[3] Indeed, anyone who has had the slightest acquaintance with the unprecedented human carnage brought on by the allure of crack cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine, new potent strains of marijuana, abused opioids, or any number of other substances in the pharmacopoeia of intoxicants misused for cheap “pleasures” understands the insidious and pernicious decay that dope spawns in the individual and in society.

Most “experts” promoting a “bold” or “compassionate” solution, well-meaning as they might be, either claim some expertise in a wholly unrelated field, or—more likely—possess no expertise whatsoever. They are like Saddam Hussein (before he was introduced to his Maker by the United States Army), who claimed some mantle of martial prowess owing simply to his authoritarian stature. Asked once about the dictator’s supposed military expertise, General Norman Schwarzkopf replied: “As far as Saddam Hussein being a great military strategist—he is neither a strategist, nor is he schooled in the operational art, nor is he a tactician, nor is he a general, nor is he a soldier. Other than that he’s a great military man.”[4] Those who stridently demand an end to the so-called war on drugs exhibit remarkable ignorance. They also reveal an arrogant and casual disregard for both the user and our society in order to pander to a temporary and specious desire by a selfish minority intent on exercising “rights” divorced from corresponding duties. Such ideas are not, in fact, new, but actually represent a timid surrender to human weakness and base desires with no regard for the future and only contempt for the lessons of the past.

Throughout our nation’s one-hundred-year struggle to limit the menace of psychoactive drugs, beginning with the Harrison Narcotics Act of 1914, we have continuously sought a social and legal equilibrium between maximizing individual liberty and maintaining the essential requirement of public safety and order. Along the way, we have made mistakes. We have allowed excesses and undue pendulum swings at both ends of the spectrum. We have at times witnessed government missteps, but, far more often, we have experienced tragedy and harm produced by radical self-indulgence and human predation. We constantly strain to find just the right incremental adjustments, just the right balance to maintain both liberty and order. Clearly, our current drug-control paradigm falls far short of complete success. It is, however, like Sir Winston Churchill’s famous observation about democracy: the worst system ever devised by the wit of man—except for all the others![5] Despite the selfish and pedantic complaints from the pro-drug lobby that persist in decrying our current situation, the truth is that, given the state of human nature and the profound allure of pharmacological “pleasure,” all of the activists’ novel alternatives are either politically unfeasible or dangerously irresponsible. The unintended consequences of their simplistic and irrational “solutions” would produce overwhelming social and economic costs, especially to society’s most vulnerable and innocent.

Our current drug-control policies and laws are the direct evolution and reflection of a careful understanding of humankind’s history with illicit substances and a rational assessment of man’s neurobiological and moral nature. Like Judge Learned Hand’s description of law itself, they are akin to “a monument slowly raised, like a coral reef, from the minute accretions of past individual decisions.”[6] And, notwithstanding the great challenges we still face, those laws and policies have been, given the possible alternatives, extraordinarily successful at keeping illegal drugs beyond the mainstream. Our balanced approach, combining both supply and demand reduction efforts, recognizes the need for and the efficacy of comprehensively investing in enforcement, prevention, and treatment—the tough and compassionate model conceived and implemented by Richard Nixon. Rather than initiating a drug “war,” Nixon pioneered the investments in drug education and treatment programs that, today, are funded at approximately the same level as enforcement measures. And just as with the supply reduction component of our approach, the demand reduction measures we deliver are only partially and sporadically effective; however, they’re categorically better than any alternative. Critics of the current arrangement would do well to think analytically and rationally about the truths of illegal drug use and its nexus to crime and squalor, rather than engaging in the ceaseless and thoughtless parroting of slogans and myths.

The success of our drug policies—emulated throughout the world—is demonstrated by the long-term reductions in the rates of illegal drug use in the United States. The percentage of persons aged twelve and older in the United States who used an illegal drug in the past thirty days has decreased 38 percent from its peak in 1979, where over 14 percent of Americans were consuming one or more illicit drugs, to less than 9 percent today.[7] Characterizing this as a “failure” is not only wrong, it intends to grossly mislead and hoodwink a sometimes all too-susceptible public. To completely scrap our current laws and policies based only upon blind hope and sentimental audacity in order to alleviate the putative harms done by our prohibition of illegal drugs would not simply be reckless, it would be suicidal. Especially since it would be done on behalf of the mere 9 percent of our population who seek unimpeded forms of self-gratification, leaving the vast majority of us, in the words of Russell Kirk, “to rake from the ashes what scorched fragments of civilization escape the conflagration of unchecked will and appetite.”[8]

This book is not intended to provide a specific set of policy recommendations designed to chart a pioneering way forward in our struggle against illegal drugs. Rather, it is intended to illustrate the complexities of the problem; complexities that do not lend themselves to clever, superficial, external fixes that, usually derived from preexisting ideologies, reflect theories that many want to believe in, or worse, reflect theories that echo a veiled contempt against the very authority that allows the critics to bask in their own moral luxury of condemnation, while taking for granted the security that the very object of their contempt provides them.

Ultimately, the crisis of dope is one that is deeply rooted in the character of man and, therefore, will require a citizenry that is not only committed to self-control, civility, and mutual restraint, but also unafraid to confront those among us who infect and rot our nation from within. It will require a population willing to defy the ubiquitous social and political pressures that sponsor a kind of cultural and ethical relativism that promotes lifestyles unrestrained by moral codes and the law. And, lastly, it will necessitate the reminding of our people—often—that freedom is important not only for doing what we want but also, and especially, for doing what we ought, as Lord Acton so eloquently instructed.[9]

We cannot just surrender to this modern epidemic. Civilization must be defended. This is our society—one worth fighting for. And fight we must. Not simply with compassion and caring, although these are important facets to our panoply of reactions, but also with an aggressive and wide-ranging drug law enforcement response that upholds the rule of law and what is right against a constant onslaught of amoral predators who leave only human suffering and social decay in the wake of their never-ending pursuit of riches. To not target, arrest and imprison those who prey upon our fellow citizens—sometimes with unimaginable violence and barbarity—would not only be cowardly, it would be grossly immoral. To argue otherwise is to collude with the traffickers and the sponsors of chaos, alike. America’s law enforcers are not the bad guys. They perform the difficult and dangerous tasks that their democratically-elected legislators require them to do on our behalf. To blame them for our nation’s drug problems is to misallocate responsibility in a fundamentally mistaken way.

There is no magic bullet in our response to the dope threat. There will be no grand strategic political fix. We are engaged not in a “war,” but in a struggle, one that will be with us forever and one that will require all of us to take a stand for what constitutes right and acceptable behavior in society. It means encouraging, or sometimes changing, behavior at the individual level, not in the larger, abstract sense where it becomes the responsibility of some faraway institution or agency. In every society, there are people who are consistently good and others who are irretrievably wicked. Yet the vast majority of people fall within that large middle ground, and their behavior is profoundly influenced by the moral environment of the time. That is why it is enormously important that our laws, our popular culture and, most importantly, our leadership reflect the virtuous expectations of our citizens; expectations that, at bottom, must encompass both a sense of inner-control and a degree of empathy for one’s fellow citizens. The only long-term answer to controlling the drug contagion is that which is incontestably the hardest; that is, shaping proper conduct among citizens.

The late social scientist James Q. Wilson—from whom much inspiration for this book is derived—understood that crime and other anti-social behaviors are predominantly based upon individual choice. People choose to use or traffic in drugs because they prefer such actions over their perceived consequences.[10] Thus, reflecting countless others throughout history who have contemplated the issue, Wilson understood that the only two ways to affect wrongful behavior are to change the risks associated with said behavior or to change the capacity for self-control in would-be offenders.[11] Government, through laws, can initiate the former, but it cannot replace the essential requirement for the latter. Increasing the penalties for selling crack certainly changed the risks associated with trafficking dope and greatly reduced its distribution throughout the country. Yet, even more significant to the drug’s fading popularity was a regeneration of individual restraint, no doubt helped along by the ubiquitous sight of a horrendous proliferation of “five-dollar crack whores”[12] in our cities.

The epidemic of dope is constantly held in check by both the objective risk of punishment and the subjective sense of wrongdoing. Drug laws will always be necessary, but our greatest reduction in recreational drug taking and the addictions that inevitably follow will come from our collective efforts to inculcate and reinforce within our existing and latent citizens a sensibility toward personal responsibility and an internalized prohibition against illegal and unsafe chemical indulgences. Furthermore, in addition to legal punishment, which serves as a kind of moral education to all, we must not shy away from demanding standards in our society. Not to moralize, but to maintain values that are moral and demand accountability to minimum levels of ethical criteria from our peers, our celebrities, our media, our academics and our elected officials. We must no longer be afraid to criticize and stigmatize behaviors that are injurious to us all and, therefore, merit our scorn. Together, we must resuscitate, in the words of Edmund Burke, that valuable “censorial inspection of the public eye”[13] if we are to assure the maintenance of our fragile social order.

Faced with a convergence of evil, single-minded drug traffickers both foreign and domestic, pro-drug zealots with deep pockets and big microphones, and feckless leadership in Washington, D.C., we can no longer simply assume that our children will emerge unscathed growing up in a wasteland of popular culture. It is time that we reclaim our culture and our civilization. It is time that we demand personal responsibility and the control of destructive impulses among our citizens instead of excusing or “medicalizing” them. It is time that we regain the ability and the expectation to police ourselves—a concept disparaged and discarded since the Sixties.

Jimmy Capra, the former chief of operations for the Drug Enforcement Administration, was quite right to preach to his troops that, “every night, in your city, there are parents praying that their children not get exposed to drugs. You are the answer to those prayers!” Of course, he was speaking to narcs, those intrepid and overwhelmed souls charged with enforcing our national and international drug laws, but the lesson applies to us all. We are engaged in a mighty struggle, one that demands our attention and our action. And in the words borrowed from the forty-fourth president of the United States, it is a struggle that demands we choose sides. This book is intended to separate the facts from the lies, misconceptions and demagoguery. It is also intended to make the choice clear.