Rex Tomb served in the FBI from 1968 until his retirement in 2006. For most of his career he served in the Office of Public Affairs, retiring as Chief of its Investigative Publicity and Public Affairs Unit.

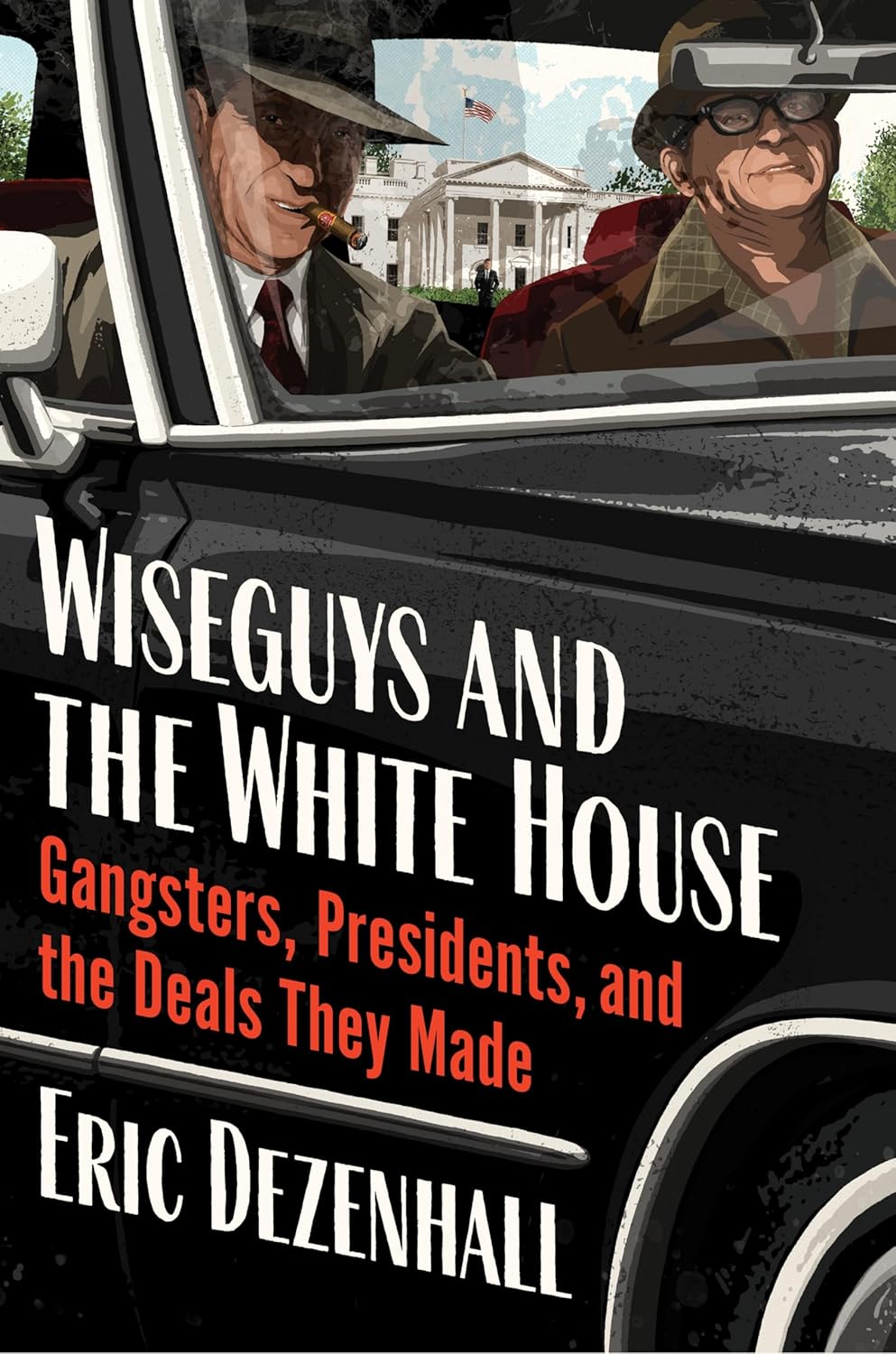

| By Rex Tomb For ticklethewire.com I recently found out that J. Edgar Hoover’s 1971 Cadillac limousine was sold on Ebay. Quickly, I went to their site and while I cannot positively confirm that it was actually the car used by Mr. Hoover, it certainly looked like the one I remembered. Just like me, it appeared somewhat worse for the wear, but was still recognizable. Seeing it was similar to reading a newspaper article about some famous actor that you thought was long dead, making a comeback. It feels oddly reassuring that something familiar still exists. Coincidentally, I had only been thinking about that car this week. In one of his recent columns, Washington Post writer, David Ignatius wrote about the seeming abundance of protective, security details. They now seem to accompany just about every high level official in Washington. Mr. Ignatius questioned whether or not this heightened security might be self defeating as it tends to draw attention. Sirens, lights, and motorcades are hard to hide. It led me to recall the security provided for former FBI Director, J. Edgar Hoover. It consisted of a bullet proof limousine and an armed driver, who although quite competent, was also quickly approaching retirement age and sported a pair of black framed, thick lens eyeglasses. That was all the protection that Mr. Hoover had as he moved through the streets of Washington, D.C. No motorcade, no sirens, no blue lights and positively no squadron of dark suited guys wearing earphones and sunglasses. Just a Cadillac and a middle-aged driver wearing those thick lens specs. We live in a much different time of course, and with absolutely zero expertise in the field, I would be the last person to second guess the necessity of providing heightened security for high government officials. Whatever the case, I remember that car, alright. It was parked in a corner of the Justice Department garage in downtown Washington. We clerks would see it on our way to and from the cafeteria. There were two Cadillac limousines, actually. One was probably a 1968, and was used as a backup. The other, parked next to it, was a brand spanking new 1971. Both cars positively gleamed. You just never saw them dirty. When it rained or snowed outside, these guys wearing smocks would suddenly appear out of nowhere and wipe them down. I always wondered how they even knew that the car was back in the garage. It was as if these guys had radar or something. Probably a secretary tipped them off. In any case, regardless of the weather, they always looked as if they had never left the building. In fact, they looked as if they were never used. There is an unfortunate perception that Mr. Hoover was like the Wizard of Oz or something. That he was forbidding, remote and would never leave his desk. He certainly had a formality about him but in fact, you would see him regularly around the Justice Department Building. His arrival at work, for instance – his big, black Cadillac would pull into the Justice Building, entering through these enormous iron gates. It always reminded me of some movie mogul arriving at his studio. The car would silently glide by the guards and those of us fortunate enough to be standing near the entrance. We could sometimes see the Boss reading a newspaper or talking to his deputy, Mr. Tolson. Mr. Tolson, by the way, was the number two man at the Bureau and the Director’s best friend. He lived along the route the Director took to his office, so I guess you could say they formed one of the most important carpools in the country! The car would then proceed down a steep ramp that went under a courtyard and into the garage. There the two would be dropped off in that corner I mentioned earlier. Mr. Hoover, or the driver, would usually help Mr. Tolson (who suffered greatly in later years from ill-health) up a short flight of steps to a door that led to an elevator bank. If you kept looking, after the Director and Mr. Tolson went through that door, you would see the driver push a small button located just above the upper left side of the door’s frame. This, I would later learn, was the infamous “garage buzz” and it would buzz in his 5th floor office suite, signaling those there that the Director had indeed arrived and that he was on the way up. To this day, I’m not certain whether or not Mr. Hoover even knew of this early warning system but it must have provided a lot of comfort to his personal staff. Mr. Hoover had no private elevator and this required him to use a public elevator to go to and from his office. It was not at all uncommon to watch some awestruck mail clerk’s jaw drop as none other than J. Edgar Hoover entered the elevator. I know this because this happened to me. One day I was taking the elevator down from the 6th floor. It stopped on the 5th and when the door opened I was utterly dumbfounded as Mr. Hoover and Mr. Tolson quickly stepped in. I was so nervous I felt like throwing up. Immediately upon entering, he cordially greeted me. Mr. Tolson remained silent. Nervous, all I could think to say was “It certainly is hot outside.” Without looking at me, Mr. Hoover replied, “Yes. I noticed that it was muggy outside when I came in this morning.” Mr. Tolson then added that “One can certainly stand in good stead with the air conditioning.” They then got off the elevator in the basement and proceeded to their waiting limo. That was the extent of my first conversation with the great Mr. Hoover and Associate Director, Clyde A. Tolson. Sparkling conversation on my part, wasn’t it? I was able to make a couple of quick observations though. First, he looked much better in person than he did in the photographs I had seen of him. Also, he had a certain presence about him. If someone saw him and had no idea who he was, they would somehow know that he was important. Some people just have an aura. He was also very tan, immaculately tailored, of average height and surprisingly trim. He had brown eyes, refined facial features and hair made dark by copious amounts of brilliantine (think Vitalis). A pretty good description of someone you saw for about 60-seconds (max), no? Mr. Hoover was also surprisingly accessible and he regularly set aside a few minutes during the week to meet with Agents, file clerks and assorted others who, along with their families, would traipse into his office to meet privately and be photographed with him. He must have understood the importance of symbolism because his office was a study in it. Everywhere you saw awards and citations that he had received from kings, presidents, civic and government organizations, police departments and major news and entertainment entities. His office was trimmed with some kind of dark wood (I was once told that it was walnut). It had a high ceiling and a large, highly polished conference table at the center under three impressive chandeliers. You had to travel a considerable distance across the room to get to his desk which was flanked by American and FBI flags. The office, while impressive, could never be described as ostentatious. Rather it conveyed a sense of substance, dignity and purpose. Mr. Hoover obviously did some homework before these meetings took place. He would often say nice things about an employee’s work in front of their families. He would also mention something about the town or city that the family had come from. Though these meetings would only last for only a few minutes they were a big morale booster and those who took part in them left very excited. After hearing several of my friends talk about their experiences, I decided that I would also ask that my father and I have an opportunity to meet with the famed Director. Checking with my mother, I found out when my father was scheduled to again be in Washington. I then submitted a standard request which was promptly approved. When I telephoned Dad to give him the good news (he was totally unaware of what I had done), he seemed, well, less than enthusiastic. First he told me that his schedule had changed and that he would not be in Washington on the day of our appointment. Then he told me that he really had no desire whatsoever to meet Mr. Hoover under any circumstances. He chided me further by adding that I could have saved everyone a lot of time and trouble by first checking with him. I was stunned but Dad was adamant, so I had to cancel the meeting. You won’t find this in any text book, but the history of this nation was probably changed by my father’s refusal to meet with Mr. Hoover (I’m kidding)! I and many of the other clerks I worked with were intensely interested in Mr. Hoover. We wanted to know everything about him and I think I can understand why. We were young, ambitious and barely in our twenties. Mr. Hoover, though old enough to be our grandfather, had several things in common with us. He was someone who came from a middle class family (many could identify with this), he was raised in a family that valued hard work and religion (many of us could identify with this), he started his Federal career as a clerk in the Library of Congress (many of us could identify with this) and he worked all day attending college at night (again, many of us could identify with this). He became the Director of a Federal agency at 29 years of age (not a whole lot older than we were) and would become a confidant of Presidents, appear on the cover of major magazines, and have Congressmen, governors, motion picture actors, recording artists, clergymen, television stars, sports figures and corporate executives lined up at his office door almost every day. He was also intimately involved in some of the most important events of the day. We really admired the fact that he never made any attempt to deny his modest beginnings. He transcended them, instead. As one friend put it to me, “. . . it’s not like this guy was born rich like a Rockefeller. He accomplished all of this on his own.” We wanted to learn what made him so successful and some of my colleagues must have found out because they went on to head up national investigations, lead major FBI Field Offices and become Assistant Directors with national and international responsibilities. After retirement, some of these same guys took on very lucrative corporate jobs. They ended up becoming national figures in their own right. Others of us, including me, never seemed to discover it and for better or for worse (mostly for better), our careers charted a more modest course. I know of course, that the mere mention of J. Edgar Hoover in some circles elicits nothing but scorn. Some of the criticism of him is doubtless justified, but a lot of it is either baseless or the critic fails to put the alleged wrongdoing in the context of the time in which it occurred. What’s that old saying about it being wrong for a person of one generation to judge the actions of a person from another generation? Others of us, and I unashamedly put myself in this category, admit that Mr. Hoover had his faults but we believe he also brought to the table innovation, hard work, discipline, persistence and a keen intellect. He was not ostentatious. That big office and the awards on the walls were there to inspire confidence and demonstrate substance rather than to impress. That’s an important distinction, which I think can also be said of that 1971, Cadillac Fleetwood I recently saw on Ebay. Gosh, after all of these years could that really be the car he used? If so, the new owner should be told that when that car was a little bit younger, had smoother skin and a more lustrous shine, it had more than a few secret admirers. It was also used by several of Mr. Hoover’s successors, including, L. Patrick Gray and Clarence M. Kelley. I would have tried to buy it myself, but my wife, when told of my plan asked if it was big. “Yes,” I told her, “it is, why?” “Because,” she said, “if you buy it you’ll be living in it . . . alone.” |

By Allan Lengel ticklethewire.com The classic black 1971 Fleetwood Cadillac would have been a sweet acquisition regardless. But what made it all the more appealing was the online ad on eBay with the notation “1971 CADILLAC LIMOUSINE – (J. EDGAR HOOVER) FBI” and a photo of a dashboard adorned with switches marked “siren” and “phone”. After a week of bidding – the first bid started at $765 — the winning bid for a piece of Americana was $6,677.77 on Aug. 7 at 9:47 p.m. The winner was Harvey Pincus, a collector of cars who runs Model Garage Inc. on 39th Street in Brooklyn, N.Y. How could he be sure it was FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s car? Pincus, who didn’t want to say much until he picked up the car, said by telephone that he saw the letter of authenticity on eBay. “There was a letter posted and I have some knowledge” of other things to verify it, he said. He declined to elaborate, and for that matter, say much more until he picks up the car. He bought the car with about 50,000 miles from Bill McDaniels of Petersburg, N.J., a man described by a friend as semi-retired, a car collector and a jack of all trades. McDaniels did not return several calls made to his cell phone. But his friend Brad Sturgess, 35, who sold the car for McDaniels, did. Sturgess said he helped sell the car on eBay because McDaniels is ” not real good with the computer and I do eBay and Craigslist and all that stuff.” Sturgess said McDaniels bought the car in recent years for $9,000 from the second person to own it since Hoover. Sturgess said McDaniels decided to sell it because he was accumulating too many cars and “It was time to liquidate.” Sturgess said the car had some unique features: separate air conditioning unit for the back seat, switches for the now-disconnected siren and phone and a “huge” generator and alternator. He said it also appeared that there was once flashing police lights in the front grille of the car. “It’s neat,” he said. “It’s older than me.” Hoover, who unquestionably is one of the most legendary of America’s law enforcement figures, had five FBI cars; two in Washington, two in New York and one in Los Angeles, according to a July 1977 Associated Press report. After Hoover’s death on May 2, 1972, the cars were sent to the General Services Administration, which turned over four to the Secret Service and put the fifth one up for auction. Denny Tiche of Boyers, Pa. bought it in 1976 for more than the $2,900 book value, the AP report said. The following year, Tiche planned to sell the car, but wanted to wait until he got a letter of authenticity. In a letter dated June 21, 1977, the FBI wrote: “The automobile in question was assigned to the late Director Hoover and, on April 22, 1976 was taken to the GSA sales center for disposal.” Tiche did not return a phone call for comment. This month, 33 years after Tiche bought the car, 26 people posted bids on eBay. “I had a bunch of people outside of the country wanted to ship it,” Sturgess said. ” I didn’t want to get involved. They were paying the same amount. Had a guy from France. Had a guy from Spain. In the end, Sturgess said he was surprised the car didn’t fetch more money. In fact, after the sale, he said someone said that the car was worth far more. But in the eBay world, he said, “”that just so happens how it works.” |