Joe Valiquette is a retired FBI supervisory special agent and J. Peter Donald is a public affairs specialist for the FBI in New York. This is the first of a three part series written for the FBI.

By Joe Valiquette and J. Peter Donald

Thirty years ago, in the heart of New York City, on the 28th floor of 26 Federal Plaza, the very first Joint Terrorism Task Force (JTTF) in the nation was established.

It was April of 1980; Supervisory Special Agent Barry Mawn would head up the newly designed task force with 10 agents from the FBI’s New York Field Office and 10 New York Police Department (NYPD) detectives.

They would pursue threats from the Armed Forces of National Liberation (FALN), the Puerto Rican Independence Movement, the Weather Underground, the Black Liberation Army, the Croatian Independence Movement, and many other domestic and international terrorist groups.

Along with pursuing these threats, some of the first investigations would be of major bank robberies perpetrated by domestic terrorist groups as well as bombings and other heinous crimes. The JTTF would be focused on continually gathering intelligence to proactively prevent attacks.

As FBI Director Robert Mueller recently said, “The New York JTTF was the first of its kind, and today, it remains among the very best of its kind. It has long been the ‘gold standard’ by which other JTTFs are modeled.”

The JTTF’s record of successful investigations, arrests, convictions, and most importantly, thwarted acts of terrorism, confirms the reputation of New York City’s JTTF as the most effective counterterrorism unit in the nation.

“The JTTF is always the first stop for any foreign elected officials or law enforcement partners visiting us from abroad” said Special Agent Pete Desai who coordinates all liaison visits. “Everyone wants to know how we do it so they can turn around and implement a similar model back home.”

Desai said several visits a month are made to the task force and stressed the importance of cooperation with law enforcement partners around the world.

New York City has long been a target for terrorists. In September 1920, suspected anarchists detonated a bomb inside a horse drawn cart on Wall Street, ultimately killing 30 people. Although methods have changed, as recently as May of this year an SUV containing a crudely made bomb failed to detonate in Times Square.

However, it was not until the 1970s that New York City experienced a consistent series of deadly attacks from several organizations as diplomatic and corporate communities became the target for terrorist groups.

They used bombs, incendiary devices, and airplane hijackings to increase pressure on the U.S. and other governments to change their policies elsewhere in the world.

Beginning in the mid-1970s, the anti-Castro Cuban group Omega 7 exploded several bombs outside the Cuban and Soviet Missions to the United Nations on Manhattan’s Upper East Side.

The FALN, a terrorist group which sought the independence of Puerto Rico from the U.S., killed several people with a bomb placed inside the historic Fraunces Tavern restaurant near Wall Street in 1975 and then killed another innocent victim in its 1977 bombing of the headquarters of the Mobil Oil Corporation on East 42nd Street.

Deaths, injuries, and property damage were not the only casualties of these terrorist acts. Deep institutional rivalries surfaced between the two law enforcement agencies tasked with keeping New York City safe—the FBI and NYPD.

The FBI’s mission had always been to protect the citizens of the U.S. and insure the security of the nation. In light of the growing number of attacks, the FBI created a squad of agents in its New York City office to investigate terrorism.

The NYPD’s mission was also to protect the citizens of New York City, and as the number of terrorist attacks increased, they began assigning additional officers and detectives from its Arson and Explosion Division to terrorism investigations.

On the surface, leaders of both agencies vowed cooperation and open lines of communication. However, not far below the surface agencies viewed one another warily and sometimes allowed professional rivalries to complicate the investigative process.

Retired FBI Agent John Crouthamel, an original JTTF member, remembered how in the days prior to the task force “there would be a competition between the FBI and NYPD to get to the crime scene first.”

At the crime scenes the same drama would always play out—witnesses would typically be interviewed twice, once by the FBI and once by the NYPD. Investigators would get in each other’s way combing through the debris of the crime scene; and, if evidence was recovered, a contest would ensue as to which agency’s lab would perform forensic tests.

NYPD detectives felt the FBI failed to work with them and FBI agents harbored similar feelings toward the NYPD.

Leaders of both agencies were keenly aware that the failure of the FBI and the NYPD to cooperate fully in these cases had to stop. Fortunately, a blueprint for an effective joint federal and city law enforcement effort already existed in the form of the FBI/NYPD Joint Bank Robbery Task Force, the first-ever FBI local law enforcement task force.

Similar to the terrorist arena, both agencies had jurisdiction to investigate bank robberies. Federally insured bank deposits provided the basis for FBI jurisdiction and the robberies were a state crime enabling the NYPD to investigate as well. The FBI had two bank robbery squads in New York City and the NYPD had the Major Case Squad.

In 1979, the FBI/NYPD Joint Bank Robbery Task Force had been created to address the alarming increase in armed bank robberies in New York City. The quick success of the task force led both agencies to believe a similar concept might also work for investigating terrorism.

In the spring of 1980, New York City Police Commissioner Robert McGuire and FBI Special Agent in Charge Joseph MacFarlane signed a memorandum of understanding creating the FBI/NYPD Joint Terrorism Task Force.

By agreement, JTTF investigations would comply with federal rules of criminal procedure and would be prosecuted in federal court.

It would be funded by the federal government and housed within the FBI’s New York City office. The NYPD detectives selected for the JTTF received security clearances giving them access to the FBI’s classified files. Additionally, they were designated as Deputy U.S. Marshals, which allowed them to carry out operations with their FBI partners outside of their New York City jurisdiction.

Instructions to the members of the newly formed JTTF from One Police Plaza and the New York FBI Office were clear—put the past aside, work together, and share all information. Many on the JTTF had doubts both agencies could work together. Retired FBI Agent Crouthamel recalled that the task force concept “didn’t sit well at first but then, over time, we became friends. The NYPD detectives brought street smarts to the partnership.”

“At the worker level, it was great”, said retired NYPD detective and original member of the task force Robert Hefner. “Everything was popping in those days, and the FBI had the resources.”

For the agents and detectives of the JTTF, the decade of the 1970s only foreshadowed the escalation of attacks for the 1980s.

Cases handled by the JTTF in those early years included:

* The investigation following the arrest in April 1980 of FALN leaders, including Carlos Alberto Torres and his wife by local police in Evanston, Illinois, leading to the discovery of a network of FALN safe houses in New York, New Jersey, Wisconsin, and Illinois. Trial preparation also began for Torres, who was later convicted in federal court in New York for the Mobil Oil bombing.

* The assassination of Cuban government attaché Felix Garcia by Omega 7 as he was driving on Queens Boulevard on September 11, 1980.

* The extensive JTTF investigation following the October 1981 armed hold up of a Brinks’ armored truck in Nanuet, New York by members of the Weather Underground and the Black Liberation Army. One Brinks guard and two Nyack Police Officers were killed. All but one of the conspirators were identified, located, and convicted.

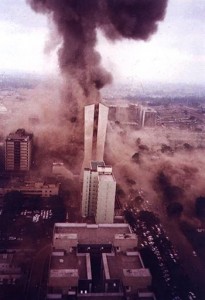

* The New Year’s Eve 1982 bombs planted by the FALN outside the FBI’s NYC headquarters at One Police Plaza, and the federal courthouses in Manhattan and Brooklyn, resulting in severe injuries to several police officers.

* The decade had the JTTF achieving the first convictions for the U.S. of members of two environmental terrorist groups responsible for a series of fire bombings of construction sites and laboratories on Long Island—the Animal Liberation Front and the Earth Liberation Front.

By the mid-1980s, the JTTF began expanding to three squads and an intelligence arm was added. Investigators from several other federal, state, and local agencies joined the FBI and NYPD on the task force as it was enlarged.