The writer, an FBI agent for 31 years, retired as resident agent in charge of the Ann Arbor office in 2006.

By Greg Stejskal

Free speech has limits, as a famous Supreme Court example illustrates. “Falsely shouting fire in a theater” is not constitutionally protected speech, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote in 1919.

(Photo: Michigan Technology Law Review)

Nearly eight decades later, the first criminal prosecution of threats on the Internet again tested the boundary of free speech. I was a player in that 1995 landmark case.

The defendant was a 20-year-old University of Michigan student who shortened his name to Jake Baker, rather than using Abraham Jacob Alkhabaz. He was described as quiet and nice, and wrote stories with innocent titles like “Going for a Walk.”

But he harbored demons. The stories were lurid, graphic tales of kidnappng, raping, torturing and killing young women – so called snuff stories. Jake posted these at alt.sex.stories, a Usenet chat group, when the Internet was in its infancy. His case raised issues we had not faced.

Urgent questions, still

Almost 25 years later, we still face the tricky, high-stakes questions: Where does freedom of speech end and when does it become a crime? How do you predict when hateful or misogynistic speech will morph into violence? Is it a crime to threaten violence?

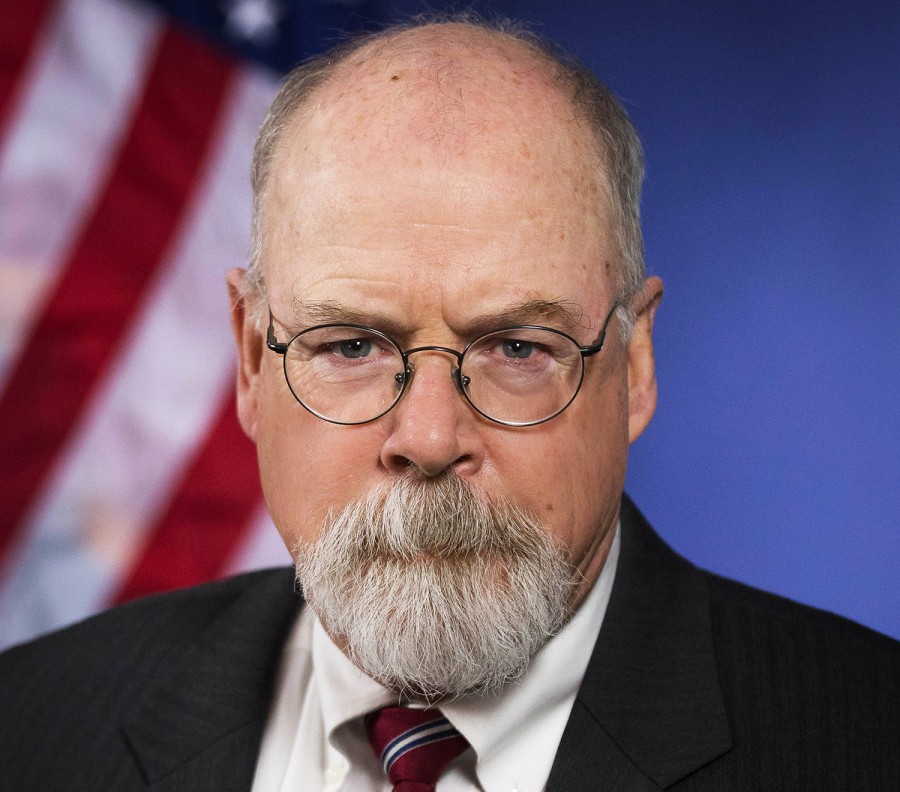

Greg Stejskal: Judge Avern Cohn “criticized the government and its ‘overzealous agent,’ referring to me.”

To examine the issue, it’s worth looking back at the federal case of United States v. Alkhabaz, a touchstone in the history of cyber law.

Back then, few people knew of the Internet. Baker’s writings were discovered thanks to a Michigan alumnus, who happened to be in Russia. He stumbled across one of Jake’s stories and knew from the IP address that Jake had some UM affiliation.

The story used the name of a real Michigan coed as a victim. (In court papers and media accounts, she was referred to as Jane Doe.) The real Jane was not aware of her characterization in the story or that she was about to be a player in a First Amendment controversy.

The alum contacted university officials, who notified the campus Department of Public Safety. Detectives talked to Jake and obtained a warrant to search his computer and email account.

‘Torture is foreplay’

Jake lived in the East Quadrangle dormitory, which also housed future mail bomber Ted Kaczynski during the mid-1960s. The search revealed several more snuff stories by Jake. Two used Jane Doe’s name and one had her address and phone number.

One story used Jane Doe’s last name in the title of the story. A paragraph in that story achieved notoriety as it appeared often in the print media. (“As an introduction to his stories, Jake wrote: ‘Torture is foreplay. Rape is romance. Snuff is climax.'”)

This is an excerpt from that story:

Then Jerry and I tie her by her long brown hair to the ceiling fan, so that she is dangling midair. Her feet don’t touch the ground. She kicks trying to hit me, Jerry or the gorund [sic]. The sight of her wiggling in mid-air, hands rudely taped behind her back, turns me on. Jerry takes a big spiky hair-brush and starts beating her small breasts with it, coloring them with nice red marks. She screams and struggles harder.

At this point the story goes from R-rated to X-rated. It ends with Jake’s protagonist lighting Jane Doe on fire.

Vivid, scary emails

The search of his email account revealed numerous messages between Jake and an individual identifying himself as Arthur Gonda, believed to be residing in Ontario, Canada.

We still face the question of where freedom of speech ends and when it’s a crime. (Graphic: DepositPhotos)

In these messages Jake and Gonda discuss actually getting together to commit the acts Jake had depicted. This is part of a December 1994 email from Jake to Gonda:

I’ve started doing is going back and rereading earlier messages of yours. Each time I do, they turn me on more and more. I can’t wait to see you in person. I’ve been trying to think of secluded spots, but my area knowledge of Ann Arbor is limited to the campus. I don’t want any blood in my room, though I’ve come upon an excellent method to abduct a bitch – As I said before, my room is right across from the girl’s bathroom. Wiat [sic] until late at night, grab her when she goes to unlock the door. Knock her unconscious, and put her into one of those portable lockers (forgot the word for it), or even a duffle bag. Then hurry her out to the car and take her away …what do you think?

This was Gonda’s response:

Hi Jake. I have been out tonight and I can tell you that I am thinking more and more about “doing” a girl. I can picture it so well … and I can think of no better use of their flesh. I HAVE to make a bitch suffer!

Jake’s response. in part:

I know how you feel. I’ve been masturbating like the devil recently. Just thinking about it anymore doesn’t do the trick … I need TO DO IT.

I saw an illegal threat

When the Washtenaw County prosecutor told campus police no state statute let the student be charged with a crime, UM’s force contacted the local FBI office.

After reading Jake’s stories and emails, I concluded that the electronic messages in context with the stories constituted a threat as defined by a federal statute [18 USC 875(c)] that deals with transmitting “in interstate or foreign commerce any communication containing any threat to kidnap any person or to injure any person.”

The statute was written long before the Internet, but that new tool clearly was an instrument of interstate commerce.

I presented the case to the Detroit U.S. Attorney’s office, which agreed with my conclusion. Our contention was that Jake had threatened not only Jane Doe, but all coeds in East Quad.

Jake was arrested on a complaint and warrant and arraigned before a federal magistrate in Detroit. We did not request detention, but after reading some of Jake’s literary works, the magistrate felt he was dangerous and ordered him kept in custody.

Fantasies are protected speech

The New York Times covered the case.

The case was assigned to District Court Judge Avern Cohn. It was apparent that Judge Cohn wasn’t a fan of the government’s case. He made it clear that Jake’s stories were protected by the First Amendment’s free speech clause and couldn’t be part of the prosecution.

So when Jake was indicted, all references to the stories were eliminated. (I argued against dropping the stories, as I believed Cohn would toss the case no matter what we did. In addition to providing context, the stories named a potential victim with her actual address.)

Cohn did dismiss the indictment, saying Jake’s emails were nothing more than a private conversation discussing fantasies and were thus protected as free speech. He criticized the government and its “overzealous agent,” referring to me.

The government appealed to the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals. A 2-1 decision by that Cincinnati court said the emails did not constitute a threat because they were “not conveyed to effect some change or achieve some goal through intimidation.”

The dissenting judge pointed out — correctly, I think — that if Congress intended proof of such an intent, it would have said so. (The appellate judges could not consider the emails in context with the gruesome stories, as they weren’t part of the indictment.)

A modern conundrum

I don’t know where Jake is now, and I have no reason to believe he ever tried to bring his horrific fantasies to life. But he might have if we hadn’t interceded. (He spent 30 days in the U.S. Marshals’ detention facility before Cohn tossed the indictment.)

In an age of terrorism, both domestic and international, law enforcement is left with the conundrum of how to address Internet communications that could be preparation for criminal acts.

Most mass shootings have been preceded by Internet postings from the shooter. The alleged El Paso shooter who killed 22 people Aug. 3 posted a white nationalist screed, saying in part: “This attack is a response to the Hispanic invasion of Texas. They are the instigators not me. I am simply defending my country from the cultural and ethnic replacement brought on by the invasion.”

His Walmart murders occurred minutes after the posting. But if no attack occurred, would the screed constitute a criminal threat that could be prosecuted?

In its effort to combat domestic terrorism, the FBI pays more attention to social media — including chatrooms and sites frequented by white nationalists, as well as sites where misogynistic messages are shared.

Chilling connection from 1995 to 2019

In 1995, we may have been on to something but didn’t know it: Misogyny — the professed hatred of women and or violent acts against women — is a characteristic of shooters in more than half of U.S. mass shootings from 2009-17.

Analysts who monitor these sites are developing profiles of potential mass shooters based on their posts. Their findings, coupled with stricter background checks and a federal red flag law, would not eliminate all mass shootings — but would stop some.

A recent example is the June 2019 arrest of Ross Farca, 23, by police in Concord, Calif., based on FBI information. Farca allegedly had made online threats to do a mass shooting at a synagogue.

He had written, in part: “I would probably get a body count of like 30 k***s (an ethnic slur for Jews) and then like five police officers because I would also decide to fight to the death.”

No date, time or specific synagogue was identified.

This alleged threat led a search warrant to be executed at Farca’s residence, whgere law enforcers found an illegally modified AR-15, 30 high-capacity magazines and Nazi literature. Farca is charged with making criminal threats and possessing an illegal assault rifle. He’s out on $125,000 bail to await trial.

Perhaps this was a mass shooting that didn’t occur because of better vigilance of the Internet and a better understanding of what constitutes a threat.