Ross Parker was chief of the criminal division in the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Detroit for 8 years and worked as an AUSA for 28 in that office.

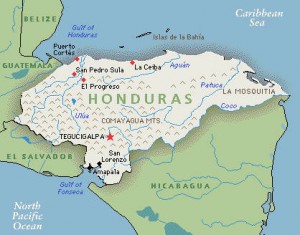

SAN PEDRO SULA, Honduras — I spent last week in Honduras with a couple dozen friends under the watchful and protective eye of a Honduran woman who has dedicated her life’s work to bettering the lives of the indigenous peasants of her country.

Despite State Department warnings we felt safe and welcome in the rural villages. The villagers were shyly courteous and grateful for any help to improve their living conditions. Their children were curious, achingly beautiful, and always up for any kind of fun activity which overcame the language barrier. They delighted in regularly beating me in lively rock-scissors-paper contests.

As in so many parts of the world today, individual Americans are well regarded here. The American government not so much. Many American NGOs, like Heifer, International and the Presbyterian Church, to name a couple, have made a real contribution in providing permanent housing, sustainable agriculture, education, and health care to the rural Mayans, whose lives have changed remarkably little in centuries.

On the flip side, Americans have played an important part in making Honduras one of the most dangerous places on the globe. It has the highest murder rate in the world. The city we flew into and out of, San Pedro Sula, is considered to be the most violent city in the world. Urban gang violence, overflowing prisons, robbery and kidnaping—all are endemic in this small country. Add to this the ancillary ills to which drug crime contributes—corruption, unstable governments, inadequate health care, and a weakened economy unable to cope with natural disasters like floods and earthquakes.

How is this, in part, the responsibility of Americans? Our insatiable cocaine habit has for decades produced the market demand fueling the multi-billion dollar export business from Colombia and Peru. With the success of U.S. law enforcement in maritime interdictions, the transit route has increasingly come through Central America to Mexico and then across our southern border. Transportation by the cartels now runs right through this relatively defenseless little country. The weak governments and overwhelmed law enforcement system are no match for the resources of the ruthless drug syndicates.

Honduras, which stretches from the Caribbean to the Pacific, is a battleground between the South American and Mexican drug cartels who violently confront each other in this neutral midpoint over territorial control and market share. Honduran bystanders become victims. All of this to get to the lucrative business of the American consumers.

We unintentionally contribute to the violence in Honduras in two other ways beyond our drug habit. Our relatively lax gun control laws make it easy for cartels to obtain in the United States assault rifles, ammunition, and other weapons to be used as deadly tools of the trade in Latin America. Not all firearms of course since civil wars have produced many left over weapons.

But enough to contribute substantially to the 40,000 Mexicans killed in the last six years. Also, our porous borders have permitted more than a million Hondurans to enter the United States. Substantial numbers have committed crimes, received a criminal education in American prisons, and then were deported back to their native country. They become drug organization recruits as well as violent criminals of opportunity.

In an era of budget tightening American politicians seem to be incrementally reducing support for international law enforcement, indeed for law enforcement in general. Statisticians point out that cocaine use is down and that drug sources have increasingly become domestic, such as meth manufacture, marijuana, and pharmaceutical drug diversion. Anyway, cocaine consumption is said to be relatively benign, victimless, a matter for education and regulation, not police and federal agents. Americans are said to have these Latin American drugs under control.

But ask Hondurans and Mexicans whether the American drug habit is benign for them. Or is it a voracious, self-obsessed monster into whose maw countless and random Latin American lives are sucked in and chewed up?

Perhaps the effect of cocaine consumption is just one symptom of the fact that few Americans give a damn about Central America. When told we were going to Honduras, most of my friends hardly knew where it was or anything about the country. But Hondurans are a proud and courageous people who deserve a safe and satisfying life as much as any American.

Through an interpreter I asked a young Honduran farmer what his hopes were for his daughter. “I dream that she will be able to get an education and live a happy, peaceful life in our village,” he replied.

I could not have stated more eloquently my dreams for my own daughter.