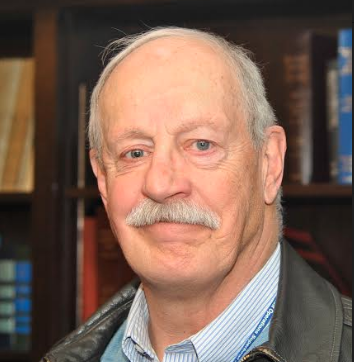

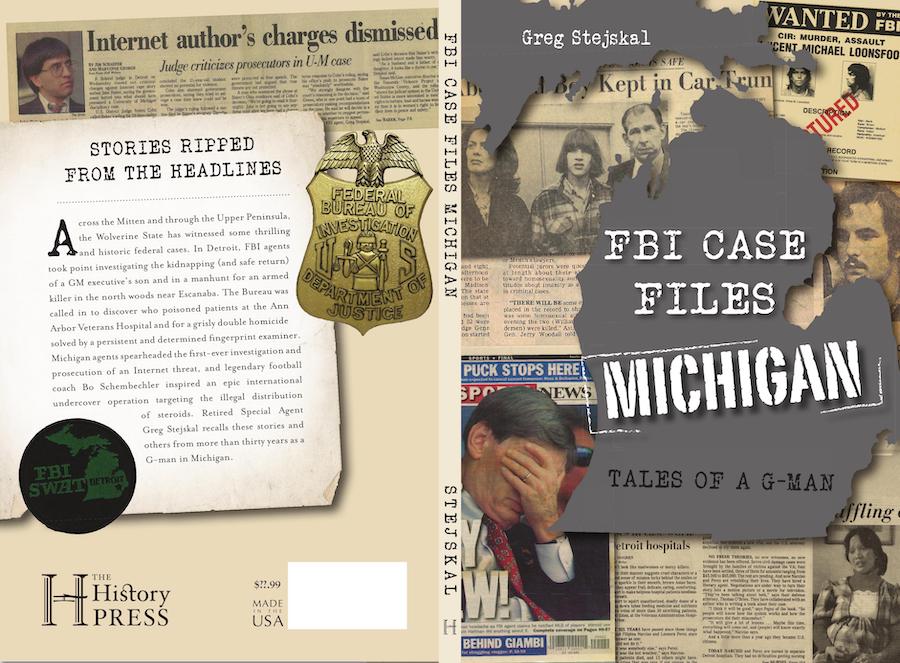

The writer, an FBI agent for 31 years, retired as resident agent in charge of the Ann Arbor office in 2006. The following is the first chapter in his book, “FBI Case Files Michigan: Tales of a G-Man,” published by The History Press. It’ll be released Feb. 21 and can be pre-ordered or found at local bookstores June 21.

By Greg Stejskal

New agent training is conducted at the FBI Academy, a sprawling complex located in the backwoods of the Quantico, Va., Marine Corps Base, about 40 miles south of Washington, D.C. My class’s new agent training was 14 weeks long, and at about the 12th week, we were told what our first office of assignment would be. Mine was Detroit—little did I know that it was to be my only office.

There was some trepidation, as neither my wife nor I had ever been to Detroit and didn’t know anyone there. Detroit is one of 56 field offices or divisions of the FBI in the United States, and Detroit Division’s territory covers the entire state. There are branch offices that are called resident agencies (RAs) spread across the state in Grand Rapids, Lansing, Flint, Ann Arbor, Marquette and several other cities.

My training ended in June 1975, and later that month, I reported to the Detroit field office. Not wanting to be late on my first day and being unfamiliar with Detroit, I got up extra early and drove to the office. I was in the office around 6 a.m. The only other people in the office were the night supervisor, an agent in charge of the night shift and a few support people.

(There is a skeleton staff in field offices 24/7. This was more important before the advent of computers and cellphones.) The night supervisor was an old-timer who regaled me with stories from his career in the bureau.

Since I was about two hours early, I was able to have a long conversation with the night supervisor before going to the front office to officially report to the special agent in charge (SAC). Each field office has a SAC, except the exceptionally large offices that are run by assistant directors.

The SAC of the Detroit office was Neil Welch. Welch was notorious in the bureau. He was known for trying to maintain his field office’s independence from FBI headquarters (FBIHQ), and because of that, there were those at FBIHQ who viewed Welch as a rogue SAC. Welch’s investigative priority was organized crime (OC), which, at that time, meant the La Cosa Nostra (LCN) or Mafia. He established the first FBI surveillance squad that was primarily tasked with collecting intelligence on the Detroit Mafia “family” (more about that in chapter 4). Later, Welch was the assistant director in charge of the New York City field office. The NYC office prosecuted some major OC and public corruption cases under his leadership. (The Abdul Scam, or ABSCAM, case was one of his cases. The movie American Hustle was loosely based on the ABSCAM case.)

Welch was not known for his warm personality. When I was ushered into his office, he was reading the newspaper, and I am not sure he stopped reading to welcome me. He told me that because I was a new agent, I would be assigned to the fugitive squad. He did pay me what I took to be a compliment by saying that he hoped to have me work OC once I was more experienced.

The fugitive squad was a great learning ground. The investigations were relatively simple—tracking down fugitives. At that time, the FBI had broad authority to arrest various categories of fugitives who were wanted for violating federal laws. But some of the most interesting and challenging fugitives were those who the FBI called UFAPs (unlawful flight to avoid prosecution). These were fugitives who had been charged by a state for committing serious crimes and then believed to have fled that state to avoid prosecution.

National Case Arrives Quickly

Often, the UFAP fugitives had been charged with murder. (Chapter 3 contains a story about one such investigation.) I had been in Detroit for about a month when, on July 31, 1975, the FBI learned that Jimmy Hoffa (James Riddle Hoffa), former president of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, had disappeared the day before. The disappearance immediately drew national attention. In investigations of this nature, there is usually a short window of opportunity.

All available Detroit agents, including me, were called in to aid in the investigation. Hoffa was last seen in the parking lot outside the Machus Red Fox restaurant, and his car was found there. The Machus Red Fox was in Bloomfield Township, a suburb in Oakland County, north of Detroit.

In what is termed a “neighborhood investigation,” the area in and around the restaurant was flooded with agents trying to find witnesses who might have seen something. Agents talked to employees and customers at the restaurant. It was difficult to identify many of the early afternoon customers from July 30, as many had paid with cash. Some were known to the employees or had made reservations. (Credit card use was not as prevalent in 1975. I have often thought that we might have had more success had there been cellphone GPS data available or the now seemingly ubiquitous security camera–recorded images.)

Six people had seen Hoffa in the parking lot, and five of the six talked to him. Hoffa never intended to go into the restaurant, and he apparently did not. The restaurant required a jacket and tie, and Hoffa had not brought either with him. One witness saw Hoffa talking to three men in a car, and another witness saw him get into the backseat of the car. The car was described as a maroon Lincoln or Mercury, and the witnesses thought this activity occurred between 2:30 and 3 p.m.

It was also established that Hoffa had called home between 2:15 and 2:30 p.m. from a pay phone outside of a hardware store next to the restaurant and asked his wife, Josephine, if Tony Giacalone had called. He told his wife that he was supposed to meet Tony Giacalone at 2:00 p.m. but that he had not arrived. It was estimated that Hoffa had left the parking lot in someone else’s car between 2:50 p.m. Jimmy Hoffa (left) and his Teamster vice president, Frank Fitzsimmons, at a rally for striking

truck drivers in 1965.

At Hoffa’s home, a note was found on his desk that read, “TG—230pm Wed 14 Mile Tel Fox Rest Maple Road.” (The time on the note was probably a mistake, as Hoffa told several people that the meeting was at 2:00 p.m.). A rudimentary timeline had been established, and we knew who set him up and why. What we did not have was any evidence of a murder, and there was no body. There’s a legal axiom that a murder cannot be proved without a body. That is not always true, but it almost always is.

After the initial investigation, it became a more traditional investigation, involving fewer agents interviewing Hoffa’s family, associates, friends, enemies and informants. A federal grand jury was used, and between September and December 1975, ninety-five individuals appeared before it.

Of these individuals, twenty-two exercised their Fifth Amendment privilege and refused to testify. The people who refused to testify were either known LCN members or Teamster officials—or both. The two original case agents were Robert “Bob” Garrity and James “Jim” Esposito, both seasoned OC

agents. They understood the dynamics of the relationship between the Teamsters and the Mafia and how it came to be.

Jimmy Hoffa was working as a truck driver in Detroit when, in 1931, he helped organize a strike of loading dock workers who off-loaded the trucks that delived produce to Kroger Grocery and Baking Co. in Detroit. Around that time, Hoffa joined the International Brotherhood of the Teamsters (a term originally used for wagon drivers). The Teamsters Union was established for truck drivers and other workers in the trucking industry.

After joining the Teamsters, Hoffa became an organizer for the union and began his meteoric rise within it. He became president of Teamsters Local 299 in Detroit. In 1957, Hoffa became the national president of the Teamsters and was primarily responsible for making it the most dominant

union in the country.

Hoffa and The Mob

Hoffa also developed a symbiotic relationship with the Mafia. Initially, the Mafia connection was concentrated in Detroit, but it involved nationwide activity. As an interconnected nationwide organization, the Mafia provided Hoffa and the Teamsters with muscle and entrance into various businesses, like construction and trash hauling. In return, Hoffa gave the Mafia access to the Teamsters’ large pension fund. The Mafia used this access to invest in casinos and hotels in Las Vegas, using front people so as not to disclose their involvement. These extremely profitable investments resulted in lucrative returns for both the Mafia and the Teamsters.

In addition to his questionable relationship with the Mafia, some of Hoffa’s other union-related activities were illegal. In 1967, Hoffa was sent to prison on federal charges of fraud, bribery and jury tampering. Hoffa was forced to cede the Teamsters presidency to his handpicked vice president, Frank Fitzsimmons. Even in prison, Hoffa retained his popularity with much of the Teamsters’ rank and file. He also continued to wield some control over union affairs. On his release from prison in 1972, Hoffa began a campaign to regain control of what he regarded as his union. But Frank Fitzsimmons did not want to step down. He had gained some autonomy by being elected as president in his own right while Hoffa was in prison; also, his Mafia sponsors were comfortable with having the much-more-malleable Fitzsimmons in charge.

As Hoffa’s frustration grew, he started making not-so-subtle threats that he would expose the Mafia-Teamsters financial relationship. It is suspected that Hoffa orchestrated the bombing of Fitzsimmons’s son’s car in the parking lot at Nemo’s Bar on July 10, 1975. Fitzsimmons and his son Richard were in Nemo’s when the car bomb exploded. Nemo’s was located a few blocks from the old Detroit Tiger’s stadium, and it was a few blocks farther from Teamsters Local 299, Hoffa’s and Fitzsimmons’s home local.

Nemo’s was a regular hangout for Teamsters officers. (Coincidentally, it was also frequented by FBI agents, especially on Fridays after work.)

If Hoffa was responsible for the bombing, it is not clear whether he intended to kill Fitzsimmons or just warn him. On July 26, Anthony “Tony” Giacalone and Vito “Billy Jack” Giacalone, both capos (short for caporegime, or captain) in the Detroit Mafia family, met with Hoffa at his residence in Lake Orion. Tony Giacalone was the primary Mafia liaison with the Teamsters. It is not known what was discussed at this meeting, but it presumably involved Hoffa’s desire to regain control of the Teamsters and the threats he had made.

Another meeting was scheduled for July 30. Hoffa believed he was to meet with Tony Giacalone—and possibly others—outside the Machus Red Fox. We know that Hoffa was there at the appointed time, but Tony Giacalone was not. Giacalone made a considerable effort to make sure people knew he was at the Southfield Athletic Club (several miles from the Machus) on the afternoon of July 30.

After Hoffa was seen getting into the backseat of a car in the restaurant parking lot, it is not known what happened to him. He was most likely killed and his body destroyed as quickly as possible. The Mafia was particularly good at making people disappear, but this was probably the most prominent,

well-known person they had ever eliminated. The probable motive for Hoffa’s murder was his threat to expose the Teamster-Mafia relationship.

The FBI’s investigation continued for years after Hoffa’s disappearance. In 1982, Hoffa was declared legally dead.

Although no one was ever charged with his murder and his body was never found, there is relative certainty about who was involved in the murder and why it happened.

Body Disposal

The Mafia was successful in eliminating a threat to their very lucrative relationship with the Teamsters and the union’s pension fund. The Mafia must have known that killing Hoffa would result in tremendous investigative pressure, which it did. The mob probably thought that by disposing of Hoffa’s body in a way that it could never be found, limiting the number of people who had knowledge of his murder and practicing omerta, the Mafia code of silence, they could weather the resulting investigation. To that extent, they were successful, but their goal of retaining access to the Teamsters pension fund was short-lived.

The FBI investigation of the Hoffa disappearance resulted in scrutiny of the corruption within the Teamsters. Ultimately, the Teamsters were temporarily placed under federal control, and many of the union’s officers were convicted of labor racketeering–related charges, including Frank Fitzsimmons’s son Richard, who had become the vice president of the Detroit Local 299. (Ironically, Jimmy Hoffa’s son, James P. Hoffa, ultimately became the national president of the Teamsters after the union was substantially purged of corruption.)

Between 1996 and 1998, the hierarchy of the Detroit Mafia family were prosecuted and convicted for violations of the Racketeering Influenced and Corrupt Organization Act (RICO). Some of the predicate acts that established a RICO case involved the Detroit family’s “secret” acquisition of casinos in Nevada. In the 1960s and 1970s, those acquisitions used money from the Teamsters pension fund. The hierarchy included both Tony and Vito Giacalone.

Vito Giacalone pleaded guilty before the trial. Tony Giacalone, who had previously been convicted of tax evasion in 1976, never stood trial due to severe medical problems. He died from heart failure in 2001.

© 2021, Greg Stejeskal