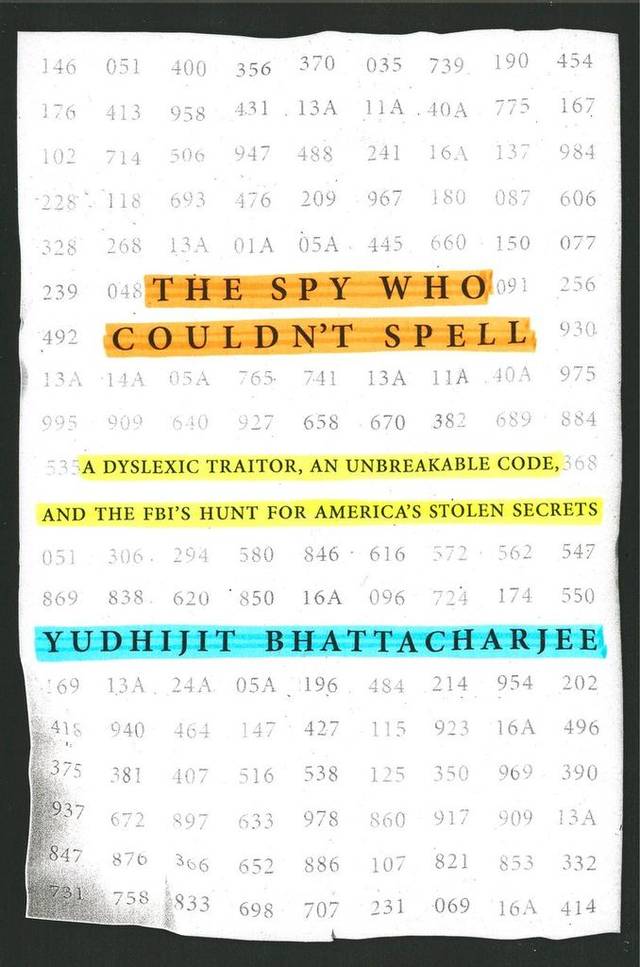

Before Edward Snowden’s infamous data breach, the largest theft of government secrets was committed by an ingenious traitor whose intricate espionage scheme and complex system of coded messages were made even more baffling by his dyslexia. His name is Brian Regan, but he came to be known as The Spy Who Couldn’t Spell. The hunt that led to Regan’s arrest began in December 2000 when the FBI was tipped off to an anonymous package mailed to the Libyan consulate in New York. The following is an excerpt from the first chapter of the book, “The Spy Who Couldn’t Spell.” Reprinted by arrangement with NAL, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2016 by Yudhijit Bhattacharjee. Links to purchase the book are at the end of the excerpt.

By Yudhijit Bhattacharjee

On the morning of the first Monday in December 2000, FBI Special Agent Steven Carr hurried out of his cubicle at the bureau’s Washington, D.C. field office and bounded down two flights of stairs to pick up a package that had just arrived by FedEX from FBI New York. Carr was 38 years old, of medium build, with blue eyes and a handsome face. He was thoughtful and intense, meticulous in his work, driven by a sense of patriotic duty inherited from his father – who served in World War II – and his maternal and paternal grandfathers – who both fought in World War I. Because of his aptitude for deduction and his intellectual doggedness, he’d been assigned to counterintelligence within a year after coming to the FBI in 1995. In his time at the bureau – all of it spent in the nation’s capital – he had played a supporting role in a series of high profile espionage cases, helping to investigate spies such as Jim Nicholson, the flamboyant CIA agent who sold U.S. secrets to the Russians.

But like most agents starting out in their careers, Carr was keen to lead a high stakes investigation himself. A devout Catholic, Carr would sometimes bow his head in church and say a silent prayer requesting the divine’s help in landing a good case. That’s why he had responded with such alacrity when his squad supervisor, Lydia Jechorek, had asked him to pick up the package that morning. “Whatever it is, it’s yours,” she had said.

Carr raced back to his desk and laid out the contents of the package in front of him: a sheaf of papers running into a few dozen pages. They were from three envelopes that had been handed to FBI New York by a confidential informant at the Libyan consulate in New York. The envelopes had been individually mailed to the consulate by an unknown sender.

Breathlessly, Carr thumbed through the sheets. Based on directions sent from New York, he was able to sort the papers into three sets corresponding to the three envelopes. All three had an identical cover sheet, at the top of which was a warning in all caps. “THIS LETTER CONTAINS SENSITIVE INFORMATION.” Below, it read, in part:

“This letter is confidential and directed to your President or Intelligence Chief. Please pass this letter via diplomatic pouch and do not discuss the existence of this letter in your offices or homes or via any electronic means. If you do not follow these instructions the existence of this letter and its contents may be detected and collected by U.S. intelligence agencies.”

In the first envelope was a 4-page letter with 149 lines of typed text consisting of alphabets and numbers. The second envelope included instructions on how to decode the letter. The third envelope included two sets of code sheets. One set contained a list of ciphers. The other, running to six pages, listed dozens of words along with their encoded abbreviations: a system commonly known as brevity codes. Together, the two sets were meant to serve as the key for the decryption.

Carr flipped through the letter, skimming the alphanumeric sequence. It looked like gibberish, like text you might get if you left a curious monkey in front of a keyboard. There was no way to make sense of it without the code sheets and the decoding instructions. By mailing the three separately, the sender had sought to secure the communication against the possibility that one envelope might get intercepted by a U.S. intelligence agency. Carr saw that the sender had included a message in typed, plain text in each envelope, informing the consulate of the other two envelopes in the mail and instructing the receiver of the message to place a car ad in the Washington Post if any of the other envelopes failed to arrive. The sender had not anticipated that all three envelopes could fall into the FBI’s hands.

FBI New York had already decoded a few lines of the letter. Carr’s pulse quickened further as he read the deciphered text.

“I am a Middle East North African analyst for the Central Intelligence Agency. I am willing to commit espionage against the U.S. by providing your country with highly classified information. I have a top secret clearance and have access to documents of all of the U.S. intelligence agencies, National Security Agency (NSA), Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), Central Command (CENTCOM) as well as smaller agencies.”

To prove that this wasn’t a bluff, the sender had included in all three envelopes an identical set of government documents, 23 pages in all, some marked “CLASSIFIED SECRET,” some “CLASSIFIED TOP SECRET.” Most of them were aerial images taken by U.S. spy satellites, showing military sites in the Middle East and other parts of the world: air defense systems, weapons depots, munitions factories, underground bunkers. Some of the documents were intelligence reports about regimes and militaries in the Middle East. It was evident from the markings on these images and reports that they had been printed after being downloaded from Intel Link, a classified network of servers that constituted the intelligence community’s Internet.

There were some additional documents. One was a monthly newsletter of the CIA, circulated internally among agency employees. Another was the table of contents of the Joint Service Tactical Exploitation of National Systems, a classified manual to help the U.S. warfighter take advantage of the country’s reconnaissance satellites and other intelligence-gathering technologies. The manual had been compromised before by another spy – an NSA cryptologist named David Sheldon Boone, who had sold it to the Soviet Union a decade earlier. In the years since, as the United States reconnaissance capabilities had evolved, the manual had been updated a number of times. The table of contents the sender had included in the package were from the manual’s most recent version. It would be valuable even to an adversary already in possession of the JTENS that Boone had given away.

Also among the documents were aerial photographs of Gaddafi’s yacht in the Mediterranean Ocean. They had been taken from a low-flying aircraft deployed not by the United States but by a foreign intelligence service. How the sender of the package could have acquired them was unclear.

Carr studied the pages in stunned silence, oblivious to the comings and goings of colleagues around him. He had never seen anything like this before. Since joining the squad, he had followed up on dozens of letters tipping the FBI off to potential espionage. Most came from anonymous sources at U.S. intelligence agencies accusing a co-worker or colleague of being a spy. Rarely did such “point and pin” letters lead to the discovery of a real threat: more often than not, they turned out to be a case of erroneous judgment by the tipster, or a case of bitter workplace jealousy.

What Carr had in front of him seemed anything but a false alarm. The sender of the envelopes was no doubt a bona fide member of the U.S. intelligence community, with access to “top secret” documents, intent on establishing a clandestine relationship with a foreign intelligence service. The person had, in fact, already committed espionage by giving classified information to an enemy country. Carr might as well have been looking at a warning sign for a national security threat flashing in neon red.

The book can be purchased at Amazon.com, Indiebound and Barnes and Noble.