This column first appeared on the substack for Christian Red. It is being republished with permission.

“You guys are doing great work,” said the person at the other end of the phone call.

I was on my way to the Capitol to secure a media credential to Thursday’s historic congressional hearing when I called one of Mark McGwire’s representatives. Big Mac, the retired Oakland A’s and St. Louis Cardinals slugger, was scheduled to testify before the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee on the steroids scourge in sports, and he was to be joined on the panel by his former A’s Bash Brother, José Canseco, as well as active players Sammy Sosa (Orioles), Curt Schilling (Red Sox), Rafael Palmeiro (Orioles) and Frank Thomas (White Sox), the latter of whom would appear by video.

Baseball’s version of a Rogue’s Gallery.

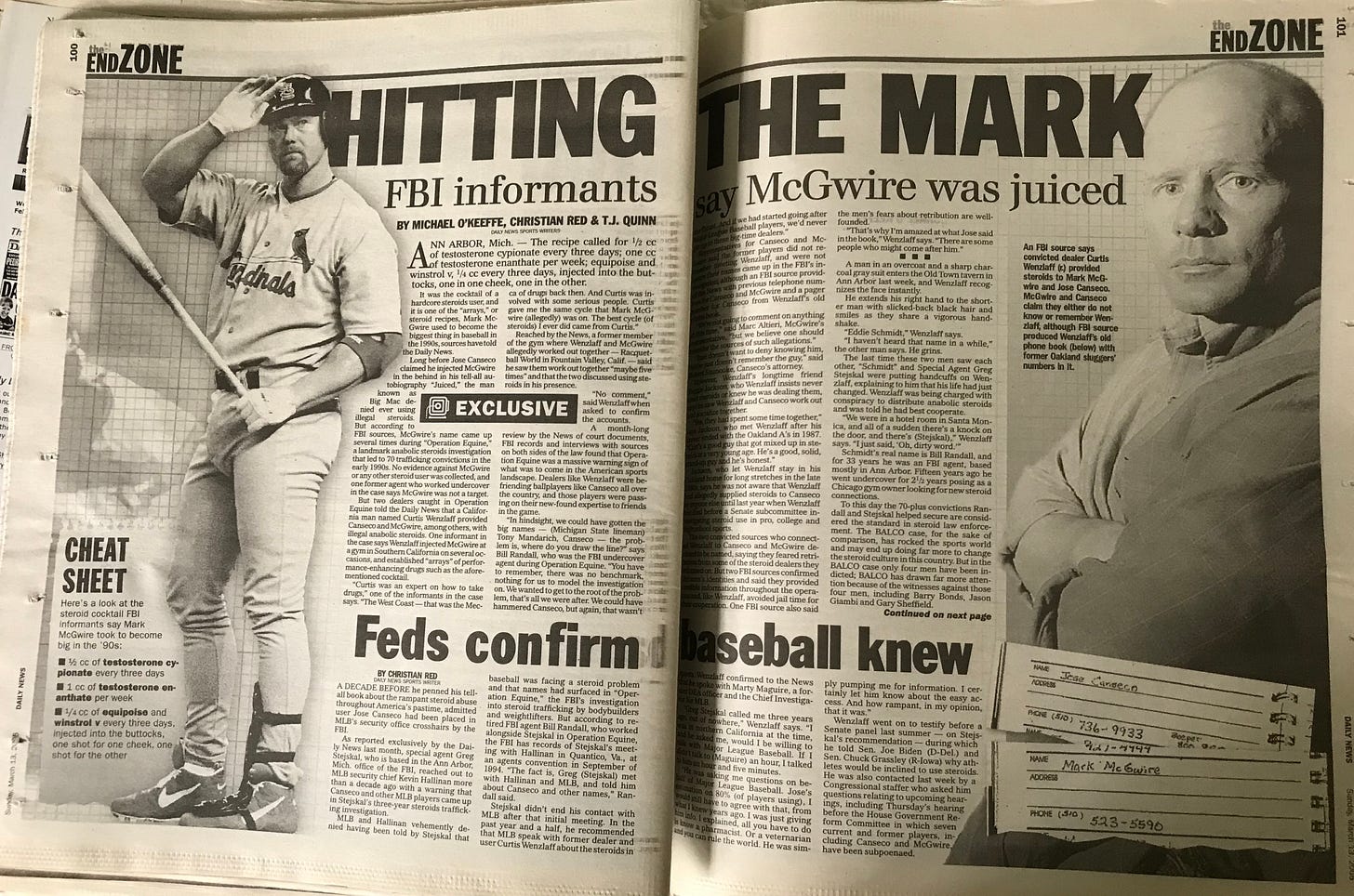

Only three days earlier, Sunday, March 13, the Daily News sports I-Team had created a big stir with our exclusive – and explosive – report on McGwire’s doping past, identifying Big Mac’s drug dealer who had designed the slugger’s hardcore steroid arrays years earlier. It was possible McGwire would be asked about his past alleged performance-enhancing drug use by the committee. Would McGwire confirm our reporting under oath?

My call to one of McGwire’s legal reps was an attempt to get that confirmation ahead of the hearing. As I braced myself for the worst, I instead got congratulations. That was better than a lawsuit, but my editor, Teri Thompson, and my News I-Team colleagues, Mike O’Keeffe and T.J. Quinn, were all scratching their heads, maybe a bit nervously, when I relayed the response.

The McGwire story was one of two I-Team exclusives we had published in advance of the hearing, and the stories came on the heels of the steroid bombshell that kickstarted 2005 – Canseco’s salacious tell-all, “Juiced,” published in February that year.

Congress was now going to insert itself into the business of America’s pastime, with committee members afforded the opportunity to grill former and active players, not to mention baseball commissioner Bud Selig, his chief labor lieutenant Rob Manfred (the current commissioner), and the players’ union executive director Donald Fehr.

Twenty years ago today, the made-for-social-media hearing unfolded in the Rayburn Building near Capitol Hill, only there wasn’t X (Twitter) or Instagram or any social media to document the play-by-play.

When the hearing began March 17, 2005, the sports world’s eyes were squarely on the two baseball retirees, Canseco and McGwire, former teammates who had slugged home runs at will during their playing days, but who also were poster boys for the so-called “Steroid Era” of baseball, at least according to the claims in “Juiced,” and in the recent reporting we had done on Big Mac.

Even before Canseco detonated the baseball world with his tome, I had cultivated a key source from a 2004 Senate hearing on steroids and sports. In a previous Substack post (https://christianred.substack.com/p/a-masked-mystery-man-a-convict-and), I wrote about Michigan native Curtis Wenzlaff, who had been a witness at that ’04 hearing. An introduction had led to a continued communication with Wenzlaff in the ensuing months. Bit by bit, I learned about his background – how he had been ensnared in a landmark steroids trafficking case from the early 1990s and his cooperation with the feds as a result of a plea deal.

Wenzlaff also steered me to the FBI agent who’d led that federal steroids probe, Ann Arbor-based Greg Stejskal, the G-Man who ultimately busted Wenzlaff. It was Stejskal who told me on the record that he had warned Major League Baseball a decade earlier about its steroid problem. Our February 2005 exclusive Daily News story had a back page that screamed, “They Knew!”

Then, in early March 2005, O’Keeffe, Quinn and I traveled to Michigan to meet with Wenzlaff, Stejskal and Bill Randall, the other FBI agent who had gone undercover during the investigation, called “Operation Equine.” The look on Wenzlaff’s face when he walked into the Ann Arbor restaurant and came face to face with the towering Stejskal and Randall was priceless. It was the first time he’d seen both agents since he was arrested in 1992.

Our report detailed Wenzlaff’s association with both McGwire and Canseco, how Wenzlaff had stayed at Hall of Famer Reggie Jackson’s Oakland home in the late 1980s, when Jackson’s career ended and McGwire’s and Canseco’s were just heating up, and how Wenzlaff used a cattle prod as a motivational technique during workouts during his early steroid education days.

Not a misprint.

Although Wenzlaff wouldn’t go on the record about his drug relationship with McGwire, we had confirmed that association through multiple sources. We felt confident about our reporting, and prior to the opening statements, I received another congratulations while roaming the halls of the Rayburn building, this one from Jack Curry, who was then the national baseball writer for the New York Times.

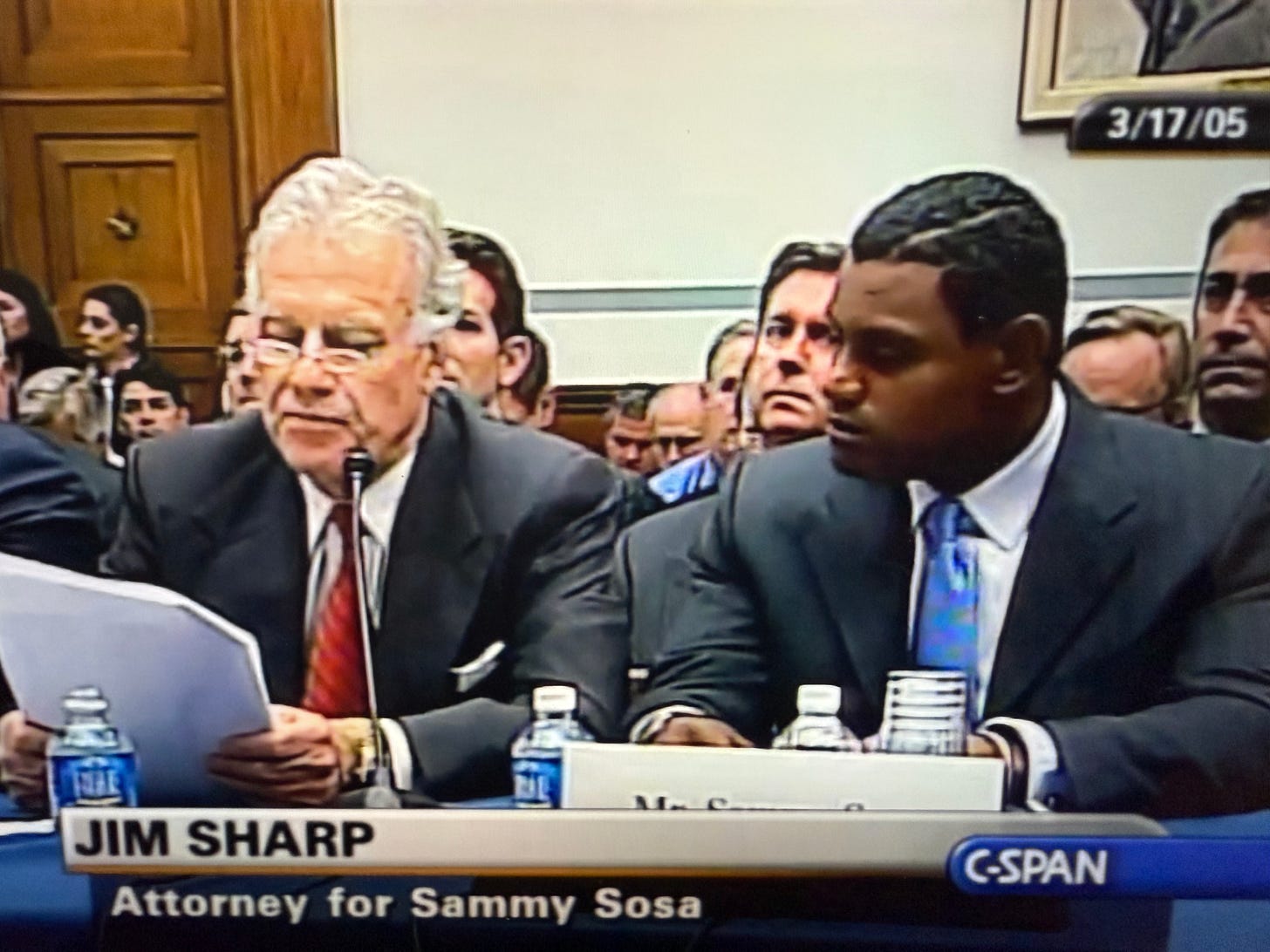

Canseco, the outcast among the group of player witnesses, took his seat on one end of the oblong table, while his attorney Robert Saunooke sat beside him. To Canseco’s left were Sosa, his attorney Jim Sharp, and Sosa’s interpreter, then McGwire, Palmeiro and finally Schilling at the other end.

Canseco was the first to give an opening statement. In old CSPAN video footage of the hearing, Canseco’s name is misspelled “Conseco” in the chyron below his face, a cruel technical flub that is symbolic in a way, given how Canseco was reviled by the majority of the baseball world at the time. The old video also shows Selig and Manfred hovering over Canseco’s shoulder, like a two-headed Dr. T.J. Eckleburg from “The Great Gatsby.”

(https://www.c-span.org/program/house-committee/steroid-use-in-baseball-players/145003)

Saunooke, Canseco’s attorney, told me in a recent interview that his and Canseco’s biggest concern going in was whether the self-professed “Godfather of Steroids” risked incriminating himself. Before the hearing, Saunooke said he and his client met with Tom Davis (R-Va.), the committee chair, and Henry Waxman (D-Calif.), the ranking minority member, over a steak dinner to talk shop.

“We had dinner at Smith & Wollensky with Waxman and Davis,” Saunooke said. “José’s concern was that he might be the subject of some criminal indictment. We had tried to figure out how José would not have any issues testifying. Meanwhile, we hear they’re negotiating with McGwire to get him an immunity deal. I was like, ‘What are you going to do for us?’ We walked into the hearing – we didn’t come under a subpoena – and I did not want Canseco to be spotlighted. They assured me he would be protected. Then, first round of questions, everyone’s attacking José.

“When we took a break, I said to the committee members, ‘We’re leaving. You haven’t protected my guy.’ They said, ‘You can’t leave.’ I said, ‘Really? We’re not under subpoena. If it doesn’t get better, you’ll see two big guys leaving out the back.’ ”

It got better, or at least improved enough so that Canseco and Saunooke stayed for the remainder of the proceedings. But there was plenty of dirt slung about the room.

Sosa, who had battled McGwire during the 1998 home run chase to break Roger Maris’ single-season record, was sworn in after Canseco. Sosa’s attorney, Sharp, read a statement on his client’s behalf… before Sosa took the mic moments later and delivered follow-up remarks. In English. Huh?

McGwire shed some tears in his opening statement, a prelude to his subsequent refrain throughout the proceedings, some variation of: “I’m not here to talk about the past.”

Big Mac didn’t miss a chance to take a little dig at his ex-teammate, however. McGwire said he wouldn’t dignify the contents of Canseco’s book in any way.

“It should be enough that you consider the source of the statements in the book and that many inconsistencies and contradictions have already been raised,” said McGwire. “Asking me or any other player to answer questions about who took steroids in front of television cameras will not solve the problem. If a player answers ‘no,’ he simply will not be believed. If he answers ‘yes,’ he risks public scorn and endless government investigations. My lawyers have advised me that I cannot answer these questions without jeopardizing my friends, my family and myself. I intend to follow their advice.”

McGwire concluded by “offering to be a spokesman for Major League Baseball and the Players Association to convince young athletes to avoid dangerous drugs of all sorts.”

Then it was Palmeiro’s turn. The Cuban-born Palmeiro – whose baseball career included over 3,000 hits and 569 homers – took direct aim at Canseco when he read his statement. Palmeiro had been named in Canseco’s book as a steroid user, and Canseco had even claimed that he had personally injected Palmeiro with drugs during their playing days on the Texas Rangers.

“Let me start by telling you this,” Palmeiro testified, pointing his left index finger at the committee members for emphasis, “I have never used steroids. Period. I do not know how to say it any more clearly than that. Never. The reference to me in Mr. Canseco’s book is absolutely false.”

It was the finger wag that would backfire spectacularly, as Palmeiro would test positive for Winstrol later that 2005 season. Winstrol (the street name for stanozolol) was the same powerful anabolic steroid that Canadian sprinter Ben Johnson was popped for during the 1988 Olympics, costing him his gold medal in the 100-meter dash. MLB suspended Palmeiro for 10 days, and 2005 was his last season in the majors.

When Schilling testified, he derisively referred to Canseco as a “so-called author” and ripped the claims in Canseco’s book as a “disgrace.” Schilling was the congressional golden boy that day, praised for his outspokenness on the steroid issue – past and present. There was a moment of comic levity near the end of the players’ testimony, when Connecticut Republican Chris Shays asked the panel what obligation each had to make sure no drugs were used by their teammates.

“My obligation first is to the Lord, then to my family, my family name, above any of my teammates that I’ve ever had,” said Schilling with a smirk.

Without missing a beat, Shays asked Schilling, “What do you think the Lord would want you to do?”

“To be as truthful and honest as you could be and had to be,” said Schilling.

Baseball’s drug-testing policy was only a year old when the hearing took place, but committee members still hammered away, calling for more stringent testing and penalties.

“Maybe it doesn’t go far enough,” said Davis. “The last thing you want is us making the policy, I guarantee you.”

Canseco, for one, was in favor of lawmakers stepping in to give baseball a swift kick in the arse.

“I made a mistake using steroids,” Canseco testified. “If Congress does nothing about this (issue), Major League Baseball will not regulate themselves. The Players Association will not regulate these players. That I guarantee. Sure, the Players Association and the owners disagree on most things, but when it comes to making money, they’re on the same page.”

Two decades later, has baseball – and professional sports – eradicated PEDs?

Selig appointed former Sen. George Mitchell to investigate baseball’s doping past in 2006, which led to the release of the Mitchell Report in December 2007. While he was still commissioner, Selig would always take any opportunity to tout MLB’s drug-testing policy as the gold standard, even when the Biogenesis doping scandal engulfed the sport in 2013.

“Major League Baseball has worked diligently with the Players Association for more than a decade to make our Joint Drug Program the best in all of professional sports,” Selig said in a statement when more than a dozen professional baseball players were suspended after violating the Joint Drug Agreement in 2013, due to their ties to the south Florida Biogenesis anti-aging clinic. “I am proud of the comprehensive nature of our efforts – not only with regard to random testing, groundbreaking blood testing for human Growth Hormone and one of the most significant longitudinal profiling programs in the world, but also our investigative capabilities, which proved vital to the Biogenesis case.”

But despite MLB strengthening its drug-testing policy – adding amphetamines to the list of banned substances (in 2006), for example – and implementing more severe penalties, players still continue to make ill-advised decisions. Former All-Star second baseman Robinson Canó, at one time considered to be on his way to Cooperstown, was twice suspended in the last decade for doping, including a positive test for Winstrol. He was suspended 80 games for the first transgression, and then the entire 2021 season after his second positive test. No Hall of Fame for him. Or Palmeiro.

“I think there’s always going to be steroid and PED use in professional sports,” said Saunooke.

And like Wenzlaff testified at the 2004 hearing: “As long as there are incomprehensible amounts of money paid to professional athletes, offered by economically insane professional sports team owners or sports product companies, there will continue to be a problem with anabolic steroid use.”

In other words, the money’s too good not to try and seek an extra edge.

McGwire eventually copped to his steroid sins during a 2010 interview with Bob Costas — five years after our reporting, but better late than never.

When I interviewed Big Mac for a 2022 Forbes story on Aaron Judge’s single-season home run chase, McGwire didn’t seem bothered that critics might still believe his, Sosa’s and Barry Bonds’ home run milestones are tainted due to the three men’s links to PEDs. (McGwire and Sosa hit 70 and 66 homers, respectively, in 1998, while Bonds, the home run king, hit 73 in 2001).

None of the three were voted into the Hall of Fame by the baseball writers.

“Everybody has an opinion. It’s magnified even more because of social media, but listen, they’ve never put a uniform on, they’ve never hit 65 home runs, they’ve never hit 70 home runs, never hit 73 home runs,” said McGwire. “They have no idea what it takes. You just don’t go to the plate and somebody sets it on a tee for you. It is because of a lot of hard work, a lot of intelligence in the mind, understanding what you need to do at the plate. There’s always going to be naysayers no matter what we’re gonna talk about in any sport, anything in life.”

Canseco certainly had his naysayers in 2005. Saunooke, who still practices law, said he hasn’t kept in touch regularly with Canseco over the years. Canseco published a steroid sequel, “Vindicated,” in 2008 which named more names.

“I have no ill will towards José. I think the world of the guy,” said Saunooke. “I still think he’s been treated unfairly by MLB, and there’s still a stigma attached to the steroid years.”

As for the committee members who presided over that ’05 hearing, at least one said there was much good that came out of the proceedings, and he even singled out the Daily News I-Team coverage from that time.

“Because of your work and our hearings, we brought attention to the scandal of steroids and other performance-enhancing drugs, which led to MLB to clean up their act and get serious about this problem,” said Henry Waxman, now the chairman of Waxman Strategies, a strategic communications firm.

Hey, I’ll take a congratulations any day over the alternative.