Greg Stejskal served as an FBI agent for 31 years and retired as resident agent in charge of the Ann Arbor office.

It was February, 1980 in Detroit.

I was assigned to the FBI surveillance squad (with apologies to Jack Webb and his introductions to “Dragnet”). It was very cold in the back of the van. We hadn’t yet installed a heater that would work when the van wasn’t running.

I had been driven to a spot where I could observe the ransom drop site from the small one-way window in the back of panel van. The driver had parked the van and left. He was picked up a few blocks away by one of the other surveillance cars. If anyone was watching, they would think the van was empty.

Kidnappings. It was one of many I would work in my career as an FBI agent. As I would witness, time and again, it was a lousy way for criminals to make money. Particularly as technology improved, it became clear: The business model simply didn’t work. And I thought it was worth recounting why.

In this 1980 case, my job was to watch the ransom package, which had been placed between the rear wall of a party store and a dumpster. The package contained $50,000. The “party store” (that’s what they call convenience stores in Detroit) was at the corner of Fenkell and Robeson on Detroit’s northwest side.

I had two HTs (hand held radios) with me in the van. One was tuned to the surveillance frequency. The other was tuned to the frequency of a transmitter in the ransom package. The transmitter broadcast a rhythmic tone that would speed up if the package was moved- pretty primitive by today’s technology.

The whole thing had started when Jacqueline Hempstead, the manager of a Detroit bank branch, learned that her son, Hessley, age 8, had been kidnapped on his way to school. She was called by the kidnappers and received instructions and a ransom demand. Mrs. Hempstead contacted her bank’s security officer, who alerted the Detroit Police Department (DPD) and the FBI.

It was decided that Mrs. Hempstead would follow the kidnappers’ instructions and comply with the ransom demand. A package with $50,000 and the aforementioned transmitter was prepared.

The FBI had been positioned in a parameter around the drop site. I had been driven to a spot near the drop site before the delivery. There I could observe the delivery and provide protection to Mrs. Hempstead if necessary.

Mrs. Hempstead delivered the package without any problems. We had agents in the vicinity of the drop, but not close enough to observe the package or spook someone wanting to make a pick-up.

After I had been watching for several hours, I heard an ominous sound, a garbage truck approaching. The truck got positioned and lifted the dumpster next to the ransom package. For a moment I thought what a novel way to retrieve a ransom. But when the dumpster was replaced, it was set on the top of the package. The transmitter screeched then seemed to moan before dying completely. The package was torn open with the stacks of bills clearly visible.

I kept my vigil, but we were concerned that a passerby might see the cash. After about an hour with no apparent effort by the kidnappers to collect the ransom, we had Mrs. Hempstead retrieve the package.

In the meantime, young Hessley, who had been left unsupervised by the kidnappers at a house on Detroit’s eastside, was able to break free and call his home. Agents that were posted at the Hempstead home told him to get out of the house and go to a neighbor’s house.

He went to the neighbors and then called again. He was picked up by FBI agents and returned home. The kidnappers were identified initially from their connection to the house where Hessley was held. They were successfully prosecuted. The kidnapping was short-circuited, but the victim was returned safe and law enforcement responded quickly and performed well.

In 1975, my first year assigned to Detroit Division (Michigan), there were four kidnappings in Michigan, three of which were classic kidnappings for ransom. The other was Jimmy Hoffa, a kidnapping/murder.

It was an exciting first year on the job for me, but this was probably an inordinate number of ransom kidnappings for anywhere, including Detroit.

Before I arrived, in much earlier times, it seemed as if criminals had had far better luck with kidnapping. In Bryan Burroughs’ book, Public Enemies, America’s Greatest Crime Wave and the Birth of the FBI 1933-34, Burroughs writes that for some of the notorious gangs of the era, kidnapping was the crime of choice. John Dillinger’s gang specialized in bank robbery, but the Barker/Karpis gang preferred kidnapping.

It was the gangs’ success in their respective specialty crimes that resulted in making them Federal Crimes, and gave birth to the FBI. (Machine Gun Kelly, a member of the Barker gang, is credited with coining the “G-man” moniker for FBI agents when he was arrested by the FBI.) The FBI learned from those early experiences.

Kidnapping for ransom, out of necessity, requires a victim who is of wealth or has some access to wealth (part of the business model). Consequently, the victim will be or is often related, in some way, to a high-profile person that can be expected to have the wherewithal and desire to pay a ransom.

The Federal statute that gives the FBI jurisdiction in kidnapping cases is called the “Lindbergh law”, which arose from the highly publicized kidnapping of Charles and Anne Lindbergh’s son by Bruno Richard Hauptmann and the proliferation of high profile kidnappings elsewhere in the U.S. The Lindberghs were wealthy, but Charles may have been the most famous and beloved person in America at the time.

The Lindbergh baby was found dead after a ransom was paid. It was several years before the case was solved. The Federal kidnapping statute relies on a presumption that any kidnapping involves interstate commerce. It is a rebuttable presumption, but allows the FBI to investigate a kidnapping without having to first establish some interstate aspect.

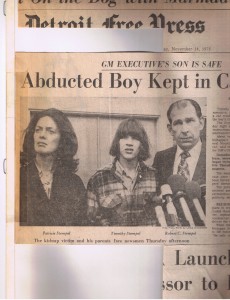

One such case came with the kidnapping in Michigan on Nov. 10, 1975. A young man, Timothy Stempel, 13, was kidnapped in Bloomfield Township, an affluent suburb north of Detroit.

Timothy’s father was Robert Stempel, a high ranking executive with General Motors (later Robert Stempel would become CEO of GM). Mr. Stempel received a series of phone calls at his home from the kidnappers, and he was told they wanted $150,000 for Timothy’s return. Stempel contacted GM security, who in turn contacted the police and FBI.

Timothy had been kidnapped by two men, Darryl Wilson and Clinton Williams, who had decided that a good money making project would be to kidnap a rich kid and hold him for ransom.

They had no specific victim in mind when they drove to the high-income neighborhood of Bloomfield Township. They passed on a few potential victims for various reasons; playing too close to a house, too young.

Then they spotted Timothy. He was skateboarding. Williams asked Timothy for directions to a person’s house. Timothy said he didn’t know the person and started to walk away. Williams pulled a handgun and told Timothy to get in the car. Timothy hit Williams with the skateboard, but Williams tackled him and struck him several times in the head. Williams and Wilson blindfolded Timothy and placed him in the backseat of the car.

They drove to Wilson’s apartment on the south side of Ann Arbor and transferred Timothy to the trunk of the car where he would remain for the next 50 some hours. Williams then called Robert Stempel and told him they had his son, and he would call back with instructions. Lastly Williams told Stempel: Don’t tell the police.

The police and FBI committed hundreds of officers and agents to the investigation. It was designated a “special” by FBI headquarters; all hands on deck. But it had to be done in such a way as to not alert the kidnappers that police were involved. The paramount goal in any kidnapping investigation is the safe return of the victim.

Robert Stempel received subsequent telephone calls on Nov. 11 and again on the next day. Ultimately, he was instructed to go to an empty lot behind a roller skating rink in Inkster, a working class suburb west of Detroit. He was to leave the money there, and he would be contacted about his son’s release.

The evening of the “drop,” it was pouring rain. Efforts were made to surveil the ransom package, but because of the location and the weather, it was impossible without taking the chance of alerting the kidnappers.

The package was retrieved, but whoever made the pick-up was not seen. (Night vision equipment would have been helpful, but was not yet available.)

Within a few hours, Timothy was released by the kidnappers not far from the drop site. Initially there were no suspects, but because much of the activity had occurred in Inkster and nearby, “neighborhood” investigations were conducted, including a canvass of businesses and homes to determine if anyone had noticed relevant activity. At an apparel store, within a block of the roller rink drop site, an agent found that two men had spent several hundred dollars in cash for clothes.

The serial numbers on the cash matched the numbers recorded from some of the ransom money, and the men who bought the clothes were identified. This is similar to how Bruno Richard Hauptmann was initially identified as the kidnapper of the Lindbergh baby. He had spent some of the ransom money, a gold certificate, at a gas station. The station attendant made a note of Hauptmann’s car license number. One of the reasons we now canvass neighborhoods.

The sartorial aspiring men were interviewed, and they told how they had agreed to drive two men to the roller rink on the night of Nov. 12 to retrieve a package containing money. The men assumed it was drug money and accepted several thousand dollars for their trouble.

The men identified Darryl Wilson and said he lived in Ann Arbor, but didn’t know his address or the other man’s name.

The investigation determined that Wilson lived in an apartment on Ann Arbor’s south side with a relative. A surveillance was set up at the apartment complex, and the car used in the kidnapping was found at the complex.

Timothy Stempel, while locked in the trunk of the car, had carved his name on the inside of the trunk lid with a broken piece of a hacksaw blade he found in the trunk- pretty ingenious.

I was assigned to the surveillance. After a few hours, one of the other agents, Stan Lapekas, suggested we take a look in a dumpster at the apartment complex for possible evidence. The dumpster was inside a wood fence enclosure in the parking lot, and we couldn’t be seen from the outside.

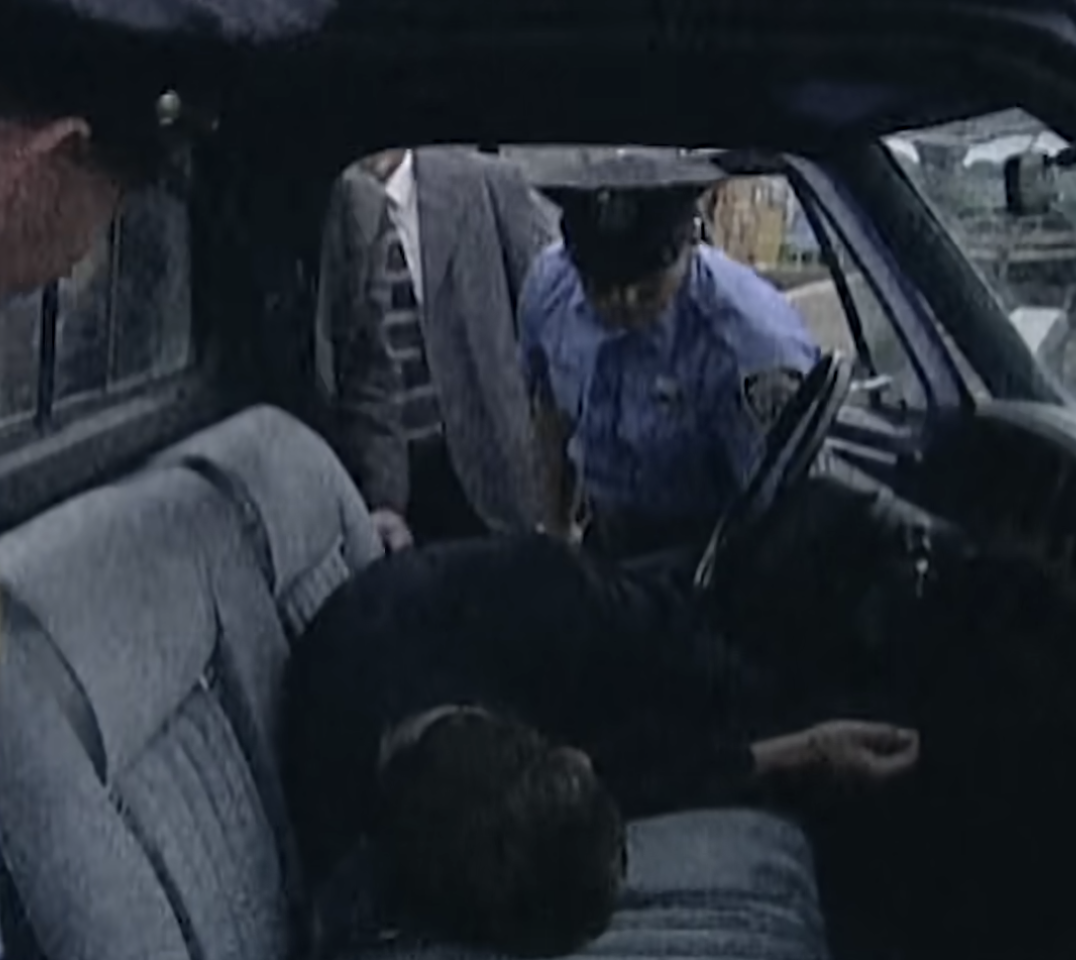

After we had been in the enclosure for only a few minutes, a car drove in and parked right next to the enclosure gate. I peeked out and realized the driver was the subject, Darryl Wilson. As soon as he exited the car, Lapekas and I grabbed him and placed him in the backseat of our car, with us sitting very close on either side of him.

We acted as if we already knew everything, but wanted to give him an opportunity to tell his side of the story. After giving him his rights, he almost immediately confessed and gave up his accomplice, Clinton Williams. We hadn’t had Williams’ name until Wilson told us. Wilson also told us where Williams lived. I got several other agents and drove to Williams’ home and arrested him.

Williams also confessed. He told us he had threatened Timothy Stempel with a handgun and hit him several times. He said they had kept Timothy in the trunk of a car for over two days. He also said he had made the phone calls to Timothy’s dad from a pay phone in Inkster. (With the existing technology, we hadn’t been able to trace the calls.)

The subsequent search of Wilson’s apartment resulted in the recovery of $137,000 of the ransom money.

The case and subsequent trial became a bit of a media circus. There was no interstate aspect of the kidnapping for it to be charged federally so it was prosecuted in State Court. The venue was Oakland County as Bloomfield Twp., where the kidnapping occurred. The high profile Oakland County Prosecutor L. Brooks Patterson, who would later run for Governor, was the prosecutor. (He is presently the Oakland County Executive.)

Because of the media attention, the trial was moved from Oakland to Leland County, in the northwest corner of Michigan’s Lower Peninsula. On the first day of trial, Patterson suspected that Wilson and Williams might be planning to enter a plea. Patterson put Timothy Stempel on the stand and introduced the trunk lid. He then had me testify out of order to get Williams’ confession on the record with all the damning admissions.

On the beginning of the 2nd day of trial, Wilson and Williams entered guilty pleas with no plea bargain.

There were several other kidnappings for ransom in the Detroit Division during my 30+ years there, but I’m not aware of any that were successful.

All the kidnappers were identified and prosecuted. In two instances although a ransom was demanded and paid, the victims were murdered. In both those cases, the kidnappers never had any intention of releasing the victims alive.

The business model for kidnapping for ransom is flawed. It is a very high-risk crime.

In some parts of the world kidnappings are done with the collusion of the police or at least their indifference, thus, lowering the risk factor. The victim has to fit a profile, and it is very difficult to successfully collect a ransom- probably more so today than in the technology challenged period of the early years of my career.

Although the potential profit would seem to be high, the odds of actually getting and keeping it are extremely low.

In the latter years of my career, there were no kidnappings for ransom in Michigan. They also seem to be rare elsewhere in the country. I doubt that kidnapping for ransom is extinct in the US, but it would seem to be on the endangered list.