By Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward

Washington Post

By Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward

Washington Post

As Sen. Sam Ervin completed his 20-year Senate career in 1974 and issued his final report as chairman of the Senate Watergate committee, he posed the question: “What was Watergate?”

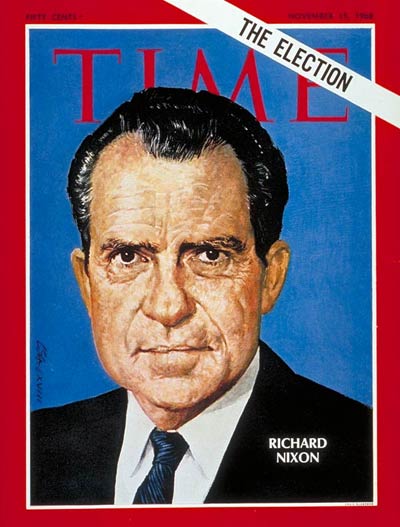

Countless answers have been offered in the 40 years since June 17, 1972, when a team of burglars wearing business suits and rubber gloves was arrested at 2:30 a.m. at the headquarters of the Democratic Party in the Watergate office building. Four days afterward, the Nixon White House offered its answer: “Certain elements may try to stretch this beyond what it was,” press secretary Ronald Ziegler scoffed, dismissing the incident as a “third-rate burglary.”

History proved that it was anything but. Two years later, Richard Nixon would become the first and only U.S. president to resign, his role in the criminal conspiracy to obstruct justice — the Watergate coverup — definitively established. Another answer has since persisted, often unchallenged: the notion that the coverup was worse than the crime. This idea minimizes the scale and reach of Nixon’s criminal actions.

To read the full column click here.