WASHINGTON — Plastic surgery is not just for the vain at heart. Recent cases show that criminals still use flesh-altering procedures to try to dodge the law. But it doesn’t always help.

Just in the past two weeks, drug traffickers from Detroit and Phoenix whose fingerprints had been surgically altered in Mexico were both sentenced to life in prison. The Detroit dealer also underwent multiple surgeries to change his face.

Meanwhile, Eduardo Ravelo, a suspected drug trafficker and hit man indicted in Texas, remains on the loose after apparently having surgery to avoid capture, authorities say.

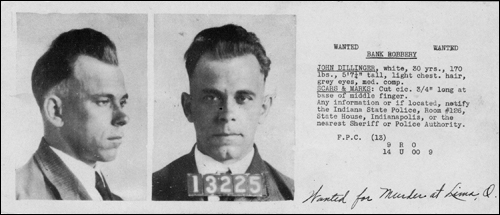

The practice is hardly new. In the 1930s, legendary bank robber John Dillinger had plastic surgery to alter his appearance. He also used acid to burn his fingerprints. But he was gunned down and killed by FBI agents on July 22, 1934, in Chicago.

But veteran Assistant U.S. Attorney J. Michael Buckley, who prosecuted the Detroit case, said the willingness to self-mutilate “shows a higher level of desperation.” Other authorities say it’s difficult to discern whether there’s been an uptick in the practice among high-level dope dealers simply based on the recent cluster of cases that have come to light.

In the Detroit case, 38-year-old Adarus Mazio Black was convicted of trafficking millions of dollars of cocaine. He used a number of aliases and obtained fake driver’s licenses in Michigan, Arizona and California. Then, authorities say, after he paid someone to knock off a federal informant in 2005, he underwent nine surgeries for his face. He also had his fingerprints altered.

“He had his fingerprints surgically removed, which the doctor said is a form of skin graft, which is very painful,” Buckley said. “He could have had the skin taken from his buttocks, but that would have alerted authorities.

“He took his toe prints and put them on the tips of his fingers,” the prosecutor said, explaining that Black wanted his fingers to look as natural as possible and have fingerprint ridges. “It’s a very painful process, and it takes a long time to heal.”

Buckley said the surgeon, a doctor from Nogales, Mexico, a town bordering Arizona, performed the surgery and testified in court in Detroit. The same doctor was sentenced last year in Pennsylvania to 18 months in prison for altering a drug dealer’s fingerprint. He was charged with hindering efforts to apprehend the drug dealer..

The prosecutor said DEA investigators did have difficulty identifying Black through fingerprints. But he said all the surgery didn’t help.

“It wasn’t effective for him,” Buckley said. ” DEA developed so much evidence against him” that they were able to nail him. Black was sentenced to life on Dec. 14.

A fingerprint specialist for the DEA in San Diego, who worked on the recent Phoenix case, said surgeons have to cut deep into the layers of the skin to obliterate the fingerprints. If not, the same distinct fingerprint ridges can regenerate and resurface. He spoke on the condition his name not be used.

In that case, evidence in trial in June showed that 62-year-old William Wallace Keegan of Palm Harbor, Fla., had all 10 fingers surgically altered in 1993 in Mexico to obliterate his fingerprints above the first joint, according to the DEA.

The DEA fingerprint specialist said the fingerprints were cut “and pretty messed up” and difficult to read. Normally, that would have been the end of the story, since in most cases authorities just take fingerprints of the first digit of the finger.

But, the fingerprint specialist said, by “happenstance the lower joints (of the fingers) happened to be on both (fingerprint) cards.” That allowed him to match the prints of Keegan, who used the alias of Richard Alan King. Keegan received five life sentences for trafficking on Dec. 10.

The FBI is still looking for Eduardo Ravelo, who was added to the agency’s Top 10 Most Wanted List in October. Ravelo is suspected of working as a hit man for the Juarez drug cartel in Mexico. He is believed to have altered his face and fingers, according to FBI agent Andrea Simmons of the El Paso office.

She said authorities don’t know for sure, but they base their suspicions on “source information”.

Obviously, altering fingerprints won’t guarantee criminals a free pass. But it can help sometimes, authorities admit.

For example, if a wanted drug dealer gets picked up for a minor offense and is fingerprinted at a police station, he may walk free hours later because the prints don’t match the ones in the database. “It’s probably going to walk them out of the first casual law enforcement encounter,” one veteran DEA agent said.

But in the end, some like the Detroit drug dealer get caught anyway, and they end up being disfigured for life from the surgery.

Said prosecutor Buckley: “He ended up with what they call drumsticks finger; his fingers were curled up and he was unable to extend them.”