WASHINGTON — In the film “Take the Money and Run,” Woody Allen played a bumbling, publicity-starved petty criminal named Virgil Starkwell. “You know he never made the Ten Most Wanted list,” Starkwell’s wife, Louise, lamented in the 1969 comedy. “It’s very unfair voting. It’s who you know.”

As Allen’s fictitious character learned, getting on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list is no easy feat. Just being a vicious criminal or a menace to society isn’t always enough.

For one, there has to be an opening. And then there’s the selection process: A committee at FBI headquarters reviews dozens of candidates from FBI field offices — there are 56 in all — before the top brass weighs in with a final decision.

“I’d be lying to say there’s no politics involved” in getting someone on the list, Tony Riggio, a former FBI agent and official, told AOL News.

In 1978, Riggio had the first organized crime figure — Cleveland mobster Anthony “Tony Lib” Liberatore — placed on the Most Wanted list. Riggio said sometimes an extra call to headquarters from a top official in the field helped get someone on the list, adding, “Being a top 10 case agent is really a feather in your cap. I got a lot of respect.”

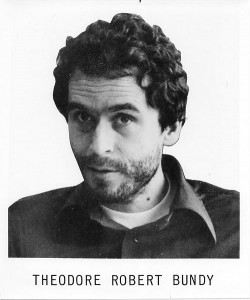

Over the years, the Ten Most Wanted alum have included some of the nation’s most notorious criminals, including escaped Martin Luther King Jr. assassin James Earl Ray, serial killer Ted Bundy and current member, Boston mobster James “Whitey” Bulger, who is wanted in connection with 19 murders. Most stay on until they are captured, a case no longer seems solid or authorities figure the person has died. Osama bin Laden was on the list up until his execution on May 1.

According to the FBI website, the list came about after a reporter for the International News in 1949 told the FBI he was interested in writing a story about the “toughest guys” the FBI was after. The FBI provided the names and descriptions of 10 fugitives — four escaped prisoners, three con men, two murder suspects and a bank robber — and the reporter wrote a story that captured national attention and triggered hundreds of tips.

Earlier this month, the bigger-than-life list, which had long become part of the American vernacular, turned 61. For decades a fixture in post offices and banks, the Ten Most Wanted photos are now more likely to pop up on TV shows, billboards and the Internet through websites and trendy social networks like Facebook and Twitter.

“We recognize the unique ability of the media to cast a wider net within communities here and abroad,” FBI Director Robert Mueller said in a statement marking the 60th anniversary. “The FBI can send agents to visit a thousand homes to find a witness, but the media can visit a million homes in an instant.”

Brad Bryant, chief of the Violent Crimes/Major Offenders Unit at FBI headquarters, says getting on the list is “very competitive.” Field offices are notified at once when an opening occurs.

“The criteria we’re looking for are, first of all, they must be particularly dangerous or be a menace to society or have a lengthy criminal history,” Bryant said.

Often, dozens of recommendations come in to headquarters, Bryant said. Field offices submit packets with information about the case, including a case file, photos and reasons why the person is worthy of joining the list. Some submissions include endorsements from local police chiefs.

The Violent Crimes/Major Offenders Unit also solicits input from the media representatives at headquarters, said Rex Tomb, who was chief of the FBI’s fugitive publicity unit in Washington until he retired from the bureau in 2006.

“Public affairs personnel like myself were generally asked by the Criminal Division to comment only on whether or not we believed there would be media interest in a fugitive,” Tomb said. “If for some reason there is little or no public interest in a particular case, reporters would generally pass on writing about it. … If there would be little print given to a Top Ten fugitive then there is really little or no reason to put him or her on the list.”

The candidates for the list are reviewed by a committee of agents from the Violent Crimes/Major Offenders unit, who carefully look over the submissions and case files.

“We rank the top four or five in the packet, and we prepare a briefing packet for the assistant director of the criminal division and his boss and the deputy director and the director,” Bryant said. Mueller must then sign off on it.

The tenor of the times has been reflected in the list over the years. In the 1950s, it hosted bank robbers. In the 1960s, some radicals made the cut, and later, organized crime figures and drug traffickers and eventually terrorists, violent gang members and sexual predators were added.

The shortest time anyone spent on the list was two hours. The longest-tenured was Donald Eugene Webb, wanted in the slaying of a police chief in Saxonburg, Pa., in 1980. He stayed on for 25 years, 10 months and 27 days before being removed in 2007. The FBI provided little reason why, only to say he no longer fit the criteria.

The oldest person ever to make the list is mobster Bulger, who got on in 1999 at age 69 and has stayed there ever since.

The list is regarded as a highly successful tool for the FBI. Of the 494 who have appeared on the list, 463 have been captured or located, with 152 of those from a direct result of citizen cooperation, the FBI said.

There are countless stories of citizens’ tips from the Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list resulting in arrests. Two fugitives were even apprehended as a result of visitors on an FBI tour who saw the photos.

Retired FBI agent Brad Garrett said that in the end, a $2 million-plus cash award — not the Ten Most Wanted listing — helped bring in information that led to the capture of fugitive Mir Aimal Kasi at a seedy hotel in Pakistan. Kasi opened fire outside CIA headquarters in Langley, Va., in 1993, killing two CIA employees and wounding three others. A few months after the shooting, he landed on the list.

“It’s an incredibly successful and novel idea, and it has captured hundreds of fugitives,” Garrett said of the famous list. “But I think it’s a lot more effective in the U.S. than outside” in places like Pakistan.

“I think the idea of a top 10 didn’t carry a lot of weight” in this case, Garrett said. “The dollar signs after his name carried a lot of weight.”