Greg Stejskal served as an FBI agent for 31 years and retired as resident agent in charge of the Ann Arbor office.

By Greg Stejskal ticklethewire.comIt was a cold early spring Saturday morning, and I was following a lead in a rural part of Michigan. I had received a call on Friday afternoon that there was a unique piece of evidence on a farm near the Michigan/Ohio border.

When I got to the farm, I made contact with the owner and identified myself. He walked me to the back of an outbuilding. There parked in the weeds was a white cargo van with flat tires. The farmer opened the van’s back door. In the middle of the cargo bay was a circular hole that had been cut in the floor.

So why was I out here on a cold Saturday morning looking at a van with a hole in its floor?

It all started in the summer the year before, 1998. An Environmental Protection Agency /FBI task force that was working illegal dumping cases had received information that a waste disposal company near Ann Arbor, Michigan, was defrauding clients by not doing work and overcharging. There were also rumors that the company was surreptitiously creating spills which they then charged clients to clean-up. The information was fragmentary, and it was coming primarily from disgruntled employees.

The disposal firm was Hi-Po. Hi-Po had been in business for about 9 years. The founders Aaron Smith, who was just 26, and Stephen Carbeck (34) started with a pick-up and a power washer. They had grown Hi-Po to more than 100 employees and several vacuum trucks at well over $200,000 each. By all accounts Hi-Po had become extraordinarily successful with such clients as the University of Michigan and Chrysler.

In the summer of 1998, the EPA/FBI task force had learned that recently one of the Hi-Po employees had quit reportedly because he was upset with Hi-Po not performing work and then charging for the work that hadn’t been done.

That employee, Michael Stagg had retired from the Washtenaw County (Michigan) drain commissioner’s office prior to working at Hi-Po. EPA agent Greg Horvath and FBI agent, Steve Flattery, both from the task force, and I went to Stagg’s home in Ann Arbor. He wasn’t surprised to see us and said he had been thinking about coming to us.

Stagg was very forthcoming, but he only had limited direct knowledge. He had inspected a Hi-Po clean-up project in Riverview, a city south of Detroit. There he saw that Hi-Po had only done about ½ the work they had contracted to do, but Stagg was told Hi-Po billed Riverview for the whole job. (Later we learned that a Riverview official was receiving kickbacks.)

Because Stagg had left Hi-Po, he had no ability to get additional evidence. He did suggest we contact Greg Cainstraight (good name for a potential cooperating witness), who had been recently hired as Hi-Po’s chief financial officer. Stagg seemed to think that Cainstraight was uncomfortable with some of the things Hi-Po was doing and might be cooperative.

Cainstraight had attended West Point and played football there. He transferred to Michigan State University where he received his accounting degree. We decided to meet Cainstraight cold and try to get a feel for whether he might be willing to work with us. It was a gamble. We did not have a strong case. If we approached Cainstraight, and he wasn’t cooperative, he could go back and warn Smith and Carbeck of the investigation. With forewarning they could make it very difficult for us to make a case.

I knew it was important to establish some rapport with Cainstraight. I talked to him about playing college football and being a West Point cadet. (I had been an undistinguished football player at Nebraska.) The West point motto, “Duty, Honor, Country” was mentioned and “The Long Gray Line,” John Ford’s movie and Rick Atkinson’s book. I think Cainstraight would have been cooperative, no matter who contacted him, but it’s important for a cooperating witness to trust the agent who handles him. We did develop a trusting a relationship, and as a result he agreed to attempt to record possibly incriminating conversations with Smith and Carbeck.

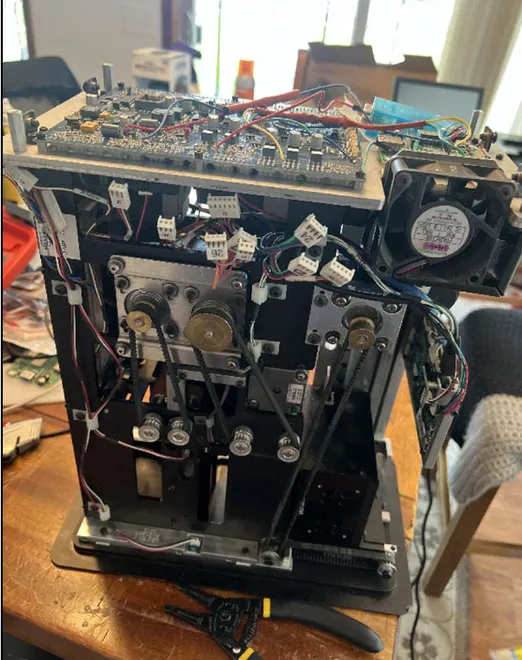

Cainstraight told us that Smith and/or Carbeck would on occasion come to his office and discuss business matters. It would not be practical to have Cainstraight “wired” all the time. (This was before miniature digital recorders were generally available. We were still using Nagra reel-to-reel tape recorders.) So we decided to wire Cainstraight’s briefcase which he told us he customarily kept next to his desk. Our tech guys put a recorder in the briefcase and made a small hole for the microphone. They also placed an exterior on/off switch so that Cainstraight could easily activate the recorder.

In September, when I delivered the briefcase to Cainstraight, we talked about recording conversations. We decided to see what transpired without trying to orchestrate any meeting. If that didn’t work, we might try to instigate something.

Within days Cainstraight called me and said he thought had recorded a good conversation. (He had no way to review the tape as Nagra’s don’t have playback capability.) “Good Conversation” turned out to be a dramatic understatement. Smith and Carbeck had come to Cainstraight’s office and for about 2 hours, held forth with a running narrative of their criminal activity at Hi-Po.

They talked about defrauding the University of Michigan. They billed UM for whole days of sewer maintenance, even though Hi-Po was doing nothing. On jobs where Hi-Po was doing work for UM and other clients they substantially over billed. They alluded to employees at UM, Chrysler and Riverview that they were bribing to play along.

But most disturbing were their stories of the incidents where they created intentional spills. Smith, as though he was telling a story about a fraternity prank, told about how he and Carbeck took a cargo van out at night with 55 gallon drums of diesel fuel. Then Smith dumped the drums through a hole in the floor of the van. Smith and Carbeck laughed when they related how the empty drums and Smith were rolling around in the back of the van as Carbeck drove away from one of the dumping sites. (Later they would anonymously report the spills to their clients, and Hi-Po would clean them up.)

Ironically, I suspect, Smith and Carbeck were trying to recruit Cainstraight to be a full-fledged member of their criminal conspiracy, and Cainstraight was recording their recruitment pitch. In my experience I had never heard nor heard of a recorded statement that was so incriminating regarding so many criminal acts. It was as though it had been scripted. One statement by Smith became notorious, “My scams are 90% foolproof.”

In October, 1998, the Assistant US Attorney, Kris Dighe, decided to get a search warrant for the Hi-Po facility. The search warrant was executed by the task force and officers from the UM Department of Public Safety. A huge amount of records were seized, and UMDPS arranged for space where the records could be stored and analyzed. The records would corroborate what many witnesses had and would tell us. They also substantiated much of Smith and Carbeck’s recorded admissions.

AUSA Dighe obtained an indictment charging Smith and Carbeck with numerous violations including RICO (Racketeer Influenced Corrupt Organization), a statute designed to prosecute organized crime which in effect Hi-Po had become. They were also charged with the predicate acts underlying a RICO charge: mail fraud; conspiracy; bribery; money laundering; intentional dumping of hazardous waste (violations of the Clean Water Act).

So that’s what brought me to that field in southern Michigan to see a forlorn van with a hole in the floor. The van wasn’t a critical piece of evidence, but it was a symbol of the “foolproof” nature of Smith’s scams.

Epilogue:

Smith and Carbeck pleaded guilty to one count each of violating the RICO Act. (I’m sure they were not enthusiastic about the prospect of hearing the recorded admissions played for a trial jury.)They were the 1st people in the US to be convicted of racketeering in an environmental case. Smith was sentenced to 33 months and Carbeck 27 months. (They had previously agreed to testify, if necessary, against other defendants.)

Smith, Carbeck and Hi-Po were ordered jointly to pay a total of $504,000 restitution to UM, Chrysler, the city of Riverview, the Budd Co. and the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality. Smith was also ordered to forfeit $500,000. Both Smith and Carbeck were also ordered to publish apologies in local newspapers.

They at least indicated they were 100% sorry.