His disappearance remains a mystery in the barrios surrounding the bustling turquoise-and-pink market on East Jefferson Boulevard. But police have long suspected George Torres, the man behind the Numero Uno grocery store chain, had something to do with it.

By the time Nacho Meza disappeared, government investigators had already spent years watching Torres, trying to bring him down on drug charges. That effort failed. But after Meza went missing, the government swept together the loose ends of its drug investigation ➤ into a 60-page indictment against Torres, including charges of racketeering, public corruption, and conspiracy to murder Nacho Meza – among others. The United States of America v. George Torres-Ramos is scheduled to begin in U.S. District Court in Los Angeles on March 10.

The indictment includes a bewildering number of names and charges – robberies, extortions, bribes, frauds – and the government’s assertion that George Torres is friends with murderers and drug runners. Former employees and associates will testify that Torres is a brutal man, even a killer, who sought to protect a criminal enterprise that was both profitable and fearsome.

But will the government be able to prove it?

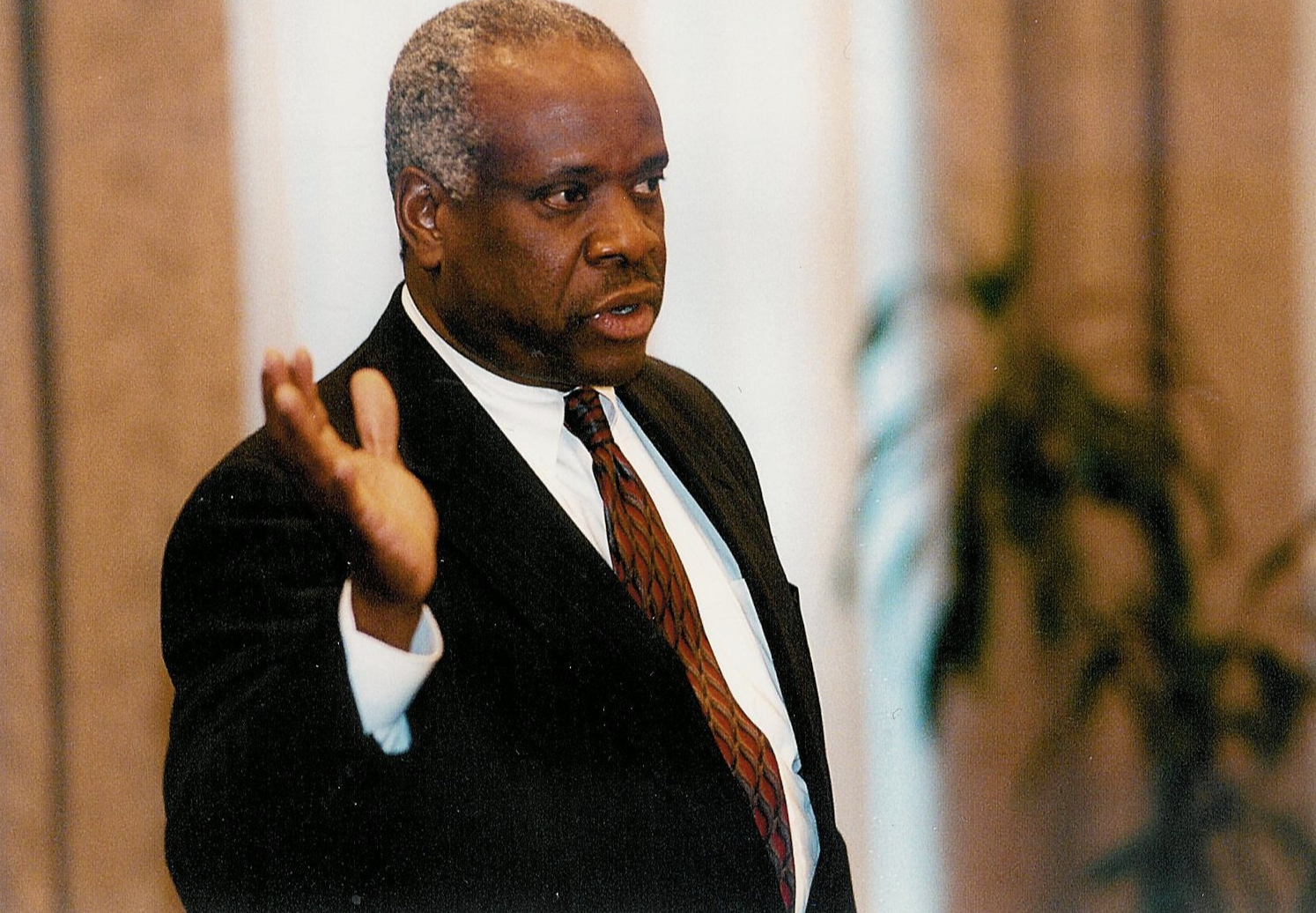

“I’ve heard the stories, listened to hours of wiretapped conversations and read more reports than I can count,” says the man who will prosecute the case, Assistant U.S. Attorney Timothy Searight, chief of the office’s narcotics division. “But I have never met a person who can put George Torres in a room with large amounts of drugs or drug money.”

So Searight turned to the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, or RICO, to charge Torres with criminal acts going back some 22 years. According to a transcript of a recent hearing before a skeptical U.S. District Court Judge Stephen V. Wilson, the result is a list of disparate charges built loosely around a theory Searight has no intention of proving: that Torres financed drug deals or laundered the proceeds of those drug deals through his supermarkets.

The RICO statute is broad, and flexible. It allows prosecutors to stitch together typically white-collar crimes – such as bank fraud or mail fraud – with murder, as long as it all relates to a central racketeering enterprise. Enacted in 1970, RICO was designed to give law enforcement a blunt tool with which to destroy the Mafia.

In the Torres case it is being used as a vehicle to prosecute a wealthy grocery store owner.

Torres will mount a formidable defense. Though his attorneys have refused City Beat’s numerous requests for interviews, it’s clear from court documents they’ll argue that the case against their client is a hodgepodge of unsubstantiated allegations, cobbled together by overzealous investigators obsessed with Torres. They say the stocky 51-year-old grocer is a hardworking father of seven with a rags-to-riches biography that began with a fruit truck and ended up with the Numero Uno grocery store chain, vast swaths of real estate on the south and eastside of L.A., dozens of houses and a Santa Ynez ranch.

FRUIT BOY

In the shadows of downtown, in crime-ravaged South L.A., it’s hard to find a wall, corner store or panel truck that gangs haven’t tagged. Ramshackle Victorian homes, chipped stucco bungalows with bars on the windows and commercial strips of bodegas, check cashing stores and carnicerias: welcome to L.A.P.D.’s Newton Division.

Over 30 years, George Torres built an empire here.

Torres was born in Tijuana in 1957 to farm workers from Michoacan, Mexico. He has lived or worked in this neighborhood most of his life. Because his father, alleged in court documents to be a brothel owner and gun smuggler, urged him to give up school early and take up the family’s produce route, Torres barely reads at a grade-school level. When he was a teenager, he sold fruit from a truck and by going door to door.

“We called him ‘Fruit Boy’ – at least if you knew him well enough you could,” said a woman we’ll call Estella; she asked that we not use her real name. She runs a little business near Maple Avenue, where Torres owns Los Amigos Mall, a yellow- and purple-painted swap meet that includes an arcade, a food court, armed security guards and stalls of vendors reminiscent of a Mexican border town.

What if you didn’t know him well enough? “You’d get your ass kicked,” said Estella.

Torres’ work ethic earned him the approval of the Flores family, owners of El Tapatio grocery stores. In 1974, Torres met his future wife, Roberta, and the couple married in 1976. In the early 1980s, with a loan from Flores and Roberta, Torres rehabbed a liquor store at the corner of Jefferson Boulevard and San Pedro Street, and stocked it with meat and produce. He called it Numero Uno. Later he opened 10 others, including stores in Cypress Park and South El Monte.

His stores are known for cleanliness and order, with no tolerance for misconduct or theft. “The employees are clean, not with baggy pants and attitude,” Estella said.

Despite the charges Torres faces, Estella is impressed with him. He’s got more than 600 employees and a chain of stores worth tens of millions of dollars, and some four dozen residential and commercial properties scattered around South L.A.

“I’ve got nothing negative to say,” she said. “If the community asked something of him, he’d respond or send someone on his behalf. He gave out food at Halloween and Thanksgiving. He goes out of his way to serve a low-income community. He had heart for the neighborhood. He opened doors to people, even gang bangers. If they burned a bridge, then it was too bad.”

Nacho Meza fit that description. A member of the Latin Hustlers gang, he had been indicted in federal court in Alabama for drug conspiracy when he disappeared. For years before he went missing, Nacho was Torres’ right-hand man. Torres set him up with Buckets, a car wash near the original Numero Uno market. Nacho, his wife and children lived in a house owned by Torres, in Downey. Law enforcement records state that Nacho used the same private jet service to transport drugs that Torres flew to Vegas to gamble.

The government’s case against Torres turns, in part, on this series of events: In 1997, Nacho’s drug activities blew up in Alabama and he went into debt. Government informants say he got desperate. One of those informants, Nacho’s former drug-dealing associate, says he and Nacho stole half a million in cash from Numero Uno one night in March 1998. The indictment says Torres retaliated by seeking to have Nacho killed.

Once Nacho was gone, Raul Del Real, his former partner at Buckets, became Torres’ right-hand man. With Torres’ help, Del Real, known as “Ra-Ra,” opened his own car wash, called the Real Deal. But like Nacho, who law enforcement documents state was deep into the drug game, Del Real, a member of the Ghetto Boyz gang who used to show up at Numero Uno frequently and meet in private with Torres, was also a dope trafficker – a violent one.

A tape-recorded conversation at L.A. County Jail on December 26, 2002, suggests that Del Real was involved in gang killings. According to a transcript of the conversation, and law enforcement reports, “a known Mexican Mafia shot caller” named Armando Ochoa tells Del Real, “My homeboys killed Lefty and now you guys got one of my homies, so let’s just call it that, right there.” A separate wiretapped conversation shows Del Real pondering his violent nature and telling his sister, “I broke a guy today.”

In 2005, Del Real pleaded guilty in a major L.A.-to-Baltimore drug conspiracy case and was sentenced to 15 years in federal prison. But not before he agreed to testify against his old friend George Torres.

‘THESE GUYS KEPT THE PEACE’

Estella came up in this neighborhood with Nacho and Ra-Ra; she said she knows of no wrongdoing on their part. While she conceded that Nacho fit a drug dealer profile, she said Ra-Ra, who has told investigators that Torres asked him to kill Nacho, is just a neighborhood character.

“George hired kids off the street,” she said. “They’ve all known each other since they were kids.”

Despite the fact that Del Real and several of his accomplices who are serving lengthy federal prison sentences ran a drug operation out of the Real Deal car wash, Estella said she never saw anything illegal. Indeed, she said, “I felt safer than ever when the guys were over there. Since George was arrested and the guys were sent to prison, the neighborhood has gone to shit. I lost a nephew [to gang violence]. That wouldn’t have happened if the guys were around. They kept the peace.”

Though Estella isn’t alone in focusing on Torres’ largesse more than the gravity of the charges he faces, she’s among his more ardent supporters.

“What is this petty crap about racketeering?” she said. “What is it about our justice system? You can’t come up so fast, so strong and be a Mexican? Everyone knows the United States is not founded on the bible, eh?” Businessmen like George Torres should be left alone, she argued. “People in this community think highly of him because of his accomplishments. He is an excellent father. He is never rude to people. I’ve never seen him dealing drugs, never seen a violent side.”

And then she lays out what could be the defense strategy: George Torres’ only crime is that he’s too kind, too loyal. If anything, she said, Torres is being maligned for his generosity, for reaching out to people like Del Real and Meza.

“They are who they are and we come from where we come from,” she said. “It’s part of the Hispanic character that you don’t get too big for your britches. George hasn’t forgotten his roots. Around here, he’ll be judged on that.”

THE PATRIARCH

Last fall, with his family in the second row of the gallery behind him, George Torres conferred with one of his lawyers in the courtroom of U.S. District Judge Stephen V. Wilson. Being stuck behind bars since his arrest in 2007 and watching helplessly as the government seized millions of dollars of his assets has altered Torres’ demeanor. His face betrayed an earnestness that wasn’t there when he was first arrested.

Civil attorney Robert Eisfelder, a longtime advisor to Torres, greeted Torres’ children and Torres’ longtime companion, Dolores Notti, who goes by “Dee Torres” and lives in a house in Arcadia owned by Torres and his wife Roberta. A young boy and girl were seated on either side of Dee Torres, and next to the young boy was Torres’ oldest son Steven, a protégé likely to inherit the Numero Uno chain, but for the fact that he too is charged with violent crimes in aid of the alleged racketeering enterprise.

Before court began, Torres turned and smiled warmly at his family. He offered a nod of encouragement to Stevie and a regretful shrug to his younger son. Torres, who turns 52 this month, still has most of his hair and deep laugh lines. He exudes charisma, even in his white prison jumpsuit with his hands cuffed beneath the table. Under different circumstances it is easy to see how his presence could be comforting, if not mesmerizing to a child.

Steven, or “Stevie,” is Torres’ oldest son by his marriage to Roberta Torres – who was not in court that day. In his gray suit, white shirt and tie, and with his arm draped over his younger half-sibling, he remained impassive throughout the hearing. Police once listened to a father-son conversation on a wiretapped call, during which Torres gave instructions on how to assault someone who threatens the family interests. “Let your daddy take care of this,” Torres told his son, according to a detention-hearing transcript.

Torres has seven children – five by Roberta Torres, who has filed for divorce, and two by Dolores Notti – and provides for them while setting an example of hard work, pride and tenacity.

Yet it was hard to imagine that his children and companion who sat in court that day know and approve of the man the government has portrayed. Their bland facial expressions suggested either they have been coached or are used to hearing (and ignoring) their father described as a bully, a thug and a gangster.

Stevie was born in 1980. Another son, Brian, was born in 1983 and recently earned a masters degree from USC. Daughter Brittany, now 19, Tawny, age 15, and son Brandon, age 14, are all in school. A law enforcer familiar with Torres says he has emphasized education with all of his children. “George has made sure that his children do not end up uneducated like he did,” the law enforcer says. “He’s a very dedicated father.”

In the early days, George and Roberta Torres were true partners, as Roberta helped with bookkeeping and banking. They worked tirelessly as they opened store after store and acquired large tracts of real estate, including industrial and commercial properties and dozens of residential properties in South L.A. and neighboring cities.

With money and success came complications to Torres’ Horatio Alger story. “She put up with a lot,” Estella says of Roberta Torres, who filed for divorce in 2005 after obtaining a restraining order and gaining custody of the couple’s two minor children. “George probably isn’t the easiest person to put up with. Where you have money you have women. But Roberta helped him build his empire. There’s no doubt about that.” Through her lawyer, Roberta Torres declined to comment.

Women, however, are the least of Torres’ troubles. His association with convicted drug-traffickers, gang members and people with ties to the Mexican Mafia and drug cartels has branded him an elusive barrio-style Godfather.

“It’s true that George is a hard worker, and that he is a family man,” says a veteran narcotics detective. “But he just can’t get that ghetto out of him. He’s always hanging with lowlifes because that’s the environment he comes from.”

THE CASE OF THE CASE THAT MISSED

Part of the government’s back file on George Torres involves the notorious Reynoso family, who, according to recently unsealed investigative reports, played a key role in Torres’ imperial rise.

Family patriarch Jose Reynoso was the owner of Reynoso Brothers International, a $37 million import-export company based in City of Industry that made headlines in the mid-1990s in connection with a major drug trafficking prosecution. The family allegedly smuggled more than eight tons of cocaine between 1991 and 1993, working with Joaquin “Chapo” Guzman and Mexico’s powerful Sinaloa cartel. The cocaine made its way through the U.S. via the Reynoso Brothers’ national food distribution network.

In 1993, Jose’s son Rene Cruz Reynoso was convicted of ordering the 1991 killing of Ronald Ordin, a Los Angeles developer and owner of the Central Wholesale Market. The investigation revealed that Ordin had threatened to evict Rene from a commercial space where Rene stored narcotics; a police report claims Rene retaliated by ordering Ordin’s murder in a drive-by on National Boulevard just off the Santa Monica Freeway in West Los Angeles.

That same year, federal prosecutors identified a member of the Reynoso family as having an interest in an Otay Mesa warehouse and canning facility situated near the end of an unfinished, 1,400-foot-long, 65-foot-deep tunnel originating in Tijuana.

Jose Reynoso was convicted in 1995 of conspiracy to traffic cocaine and was sentenced to 151 months in federal prison.

Neither Torres nor Rene Cruz Reynoso were ever charged with drug running. Government documents reviewed by City Beat identify them as alleged co-conspirators who smuggled cocaine in laundry detergent containers and jalapeño chili cans in the 1980s and 1990s, and distributed the drugs via a network of storage facilities and 18-wheel tractor-trailers. Drug Enforcement Administration reports claim that Torres worked with members of the Reynoso family to distribute 1,800 kilos of cocaine per month, at times using small customer-service buses to transport cocaine to his warehouse. Employees who saw or handled the cocaine were few and trusted, the reports state – a process so hermetically sealed that many employees were never aware of cocaine trafficking.

Despite the dramatic claims, Operation Soapbox, as the DEA investigation was called, yielded no criminal drug charges. Nor did subsequent efforts Operation Vacationer and the Robin Hood Investigation. Indeed, the government now concedes it has no evidence of Torres’ “hands-on” involvement in drug trafficking.

Yet recently unsealed wiretap affidavits, transcripts and DEA investigative reports tell a fragmented story of sanctioned killings, drive-by shootings and other violent crimes involving gang members and the drug trade, with Torres – known on the street as “Mexican George” or “G” – in the middle of it all.

The documents also show Torres using walkie-talkie phones that are hard to trace; insisting most of the time on talking in person; running cash businesses and banking with firms allegedly willing to alert him to investigations; avoiding direct contact with drugs or drug money; and allegedly threatening people who were likely to talk to police.

None of that information, however, is damning enough on its own. On the eve of trial, Searight must also rely on “the dirtiest of informants,” as Torres’ lawyers put it, to prove to a jury that Torres is an arch criminal with few peers.

But RICO statutes also permit Searight to reach as far into Torres’ past as he wants, as long he can prove a racketeering enterprise exists. Searight contends Numero Uno markets are both a front and an essential part of such an enterprise.

So far, Searight has not really said what, if not drugs, the enterprise is built on.

THEY GOT SHORTY

Santa Ana winds were blowing last September when a veteran drug task force detective took me on a ride-along through Newton Division, where the imposing Numero Uno warehouse rises like a fortress over this humble neighborhood.

“This is a real high-crime area down here,” the detective said, nodding to a group of young African Americans and Latinos who spotted him as a cop as we drove down a street lined with rundown apartments and bungalows. “George had ➤ some kind of stronghold on it.”

The detective began investigating Torres in connection with suspected drug activity in the 1980s, but is not involved in the current RICO case. We circled the block and parked across from a warehouse that stands behind a 20-foot wall with an automatic metal gate adjacent to Numero Uno on East Jefferson Boulevard. The walls of the warehouse, like the market, are turquoise with pink trim. The letters “G & R” – George and Roberta – are separated by an ampersand resembling a gun.

Rolling down the alley behind the 700 block of East Jefferson we stopped behind an auto yard covered with a tarp and surrounded by a graffiti-covered wall. Nacho Meza ran a hydraulic shop and stored dope here, according to court records. A couple blocks away, we stopped in front of the former home of Derrick “Bo-D” Smith, the drug runner turned government informant who says he and Nacho ripped off Numero Uno for half a million dollars.

In a case built around the Latino community, Smith is a rarity – an African American. He was convicted of drug trafficking in Alabama in 1999 and sentenced to 24 years in federal prison. But his criminal record dates back to the early 1980s, and includes rape, robbery and attempted murder. He’s an informant in the RICO case against Torres. According to recently unsealed investigative reports, Smith contends Meza carried out at least three killings for Torres.

In one, in 1993, a security guard who worked at Torres’ La Estrella Market on San Pedro Street was murdered. Primera Flats gang member Manuel Velasco confessed to the crime, telling detectives he shot the guard over a monetary dispute between he and Torres. (Velasco remains in prison, though he changed his story in 2004, claiming he took the rap for someone else, and that the killing had nothing to do with a monetary dispute between him and Torres.)

After the murder, the government’s case states, Torres and Meza told store employees not to speak to the police. Smith has told investigators that Nacho admitted to killing Primera Flats member Edward Carpel and injuring three others a month later, in a retaliatory drive-by shooting on East 23rd Street, around the corner from La Estrella.

Later that year, Playboys gang member Jose “Shorty” Maldonado came to Numero Uno and made extortion demands of Torres. Smith says he was at a hamburger stand outside Numero Uno with Meza and Torres when Torres turned to Meza and told him to “take care” of Shorty. Meza’s brother Jesus Meza testified before a federal grand jury on March 1, 2005, that Nacho did indeed kill Shorty, in February 1994, as Shorty was leaving a barbershop – located on property owned by Torres. Jesus testified that he drove the getaway car.

According to the government, ballistics show the same gun was used to kill Carpel and Shorty Maldonado. According to police affidavits, Smith further claims that Nacho Meza killed a third man at Torres’ behest, Roderick Chapman, in 1996.

Smith’s statements to police begin to illuminate the government’s charge that Torres eventually had Nacho murdered: Smith contends that in March 1998 he and Nacho robbed Numero Uno of $550,000 so that Nacho could pay a drug debt to former Numero Uno security guard Jose Angulo, who was dealing drugs directly for Torres. In the upside-down world of the case against George Torres, it seems Angulo knew the drug debt, which was ultimately payable to Torres, was settled with cash stolen from Torres – but he kept the money anyway.

Government documents suggest Torres smelled a rat: Interviewed after the robbery, he told detectives he suspected a former employee and that he and his associates “would take care of it themselves,” according to police reports of the interview.

A year later, on May 25, 1999, the FBI interviewed Angulo, who admitted he was Nacho Meza’s drug supplier, and confirmed that Nacho settled his drug debt shortly after the Numero Uno robbery occurred. Angulo told the FBI he never returned the money to Torres, even though he knew it belonged to him. Angulo disappeared on August 31, 1999, and has not been seen since.

FRAUD AND CORRUPTION

Searight has yet to show his full hand, but the indictment also accuses Torres of major tax fraud—alleges he skimmed $500,000 a year from his own stores’ cash registers, and extorted money from illegal immigrants who worked for him or whom he thought stole from him. The indictment also states that Torres attempted to bribe public officials—in one case attempting to bribe former L.A. City planning commissioners Steven Carmona and George Luk into securing approval for a beer and wine permit at his Alvarado Street store. In addition to a $15,000 check, the indictment states, Torres gave Carmona a GMC pickup truck and free use of his downtown condo on West 6th Street so that Carmona could qualify as a resident of that district to become a planning commissioner. In a 2004 conversation, recorded on a wiretap, Carmona and Luk agreed to ask Torres for an additional $10,000. The government claims the pair would give that money to an “unidentified official in the Los Angeles City Council” in return for support of Torres’ alcohol permit.

A 2007 Los Angeles Times story also reported that a career prosecutor in the office of City Attorney Rocky Delgadillo received pressure from Delgadillo, in 2001, to drop criminal charges against Torres for an improper demolition of low-income apartments. The prosecutor wrote in a memo, “Rocky said he was getting a lot of pressure about this case.” Torres ended up pleading guilty to a misdemeanor in the demolition case.

When a friend chides Torres about seeking favors from public officials, a wiretap transcript shows him responding: “Hey, pimp! What the fuck? Let me tell you something. If I did it the right way, I’d be broke, you know? You know what’s up, pimp?”

Torres’ talk appears to be more than just idle boasting. According to recently unsealed investigative reports, Albert Del Real, a convicted drug dealer, former Numero Uno employee and brother of Raul Del Real, says he saw former L.A. City Councilman Mike Hernandez receive “stacks of money” from Torres in the 1990s. Then-City Councilman Richard Alatorre brought his vehicle to Torres’ warehouse to get serviced, leading Del Real to tell investigators he believed that Torres, who did not provide automotive services, was doing favors for Alatorre.

Alatorre and Hernandez, neither of whom returned calls for this story, have never been charged with wrongdoing in connection with Torres. They remain City Hall fixtures. Alatorre, who pleaded guilty to felony tax evasion in 2001, is an influential lobbyist and board member of L.A.’s Best, a nonprofit that operates out of Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa’s office. Hernandez is assistant chief of staff for Councilman Bernard Parks and Councilwoman Jan Perry.

Such allegations hearken to a highly publicized national scandal involving Horacio Vignali, Torres’ former real estate partner. They also raise questions about how far Torres’ political reach was, and whether that reach helped keep him out of trouble.

Torres and Vignali, formerly two of three principles in a real estate company called Tovicep, Inc., were exposed as longtime targets of federal drug investigations in a 2002 congressional report on Pardongate, the White House scandal arising from President Bill Clinton’s grant of clemency for Vignali’s son, convicted drug trafficker Carlos Vignali Jr. The report examined revelations that, in the 1990s, Vignali was a big financial contributor who enlisted numerous politicians, including L.A. Sheriff Lee Baca, then U.S. Attorney Alejandro Mayorkas, U.S. Rep. Xavier Becerra and Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa (then a California assemblyman) to lobby Clinton for the clemency. Hernandez and Alatorre were among those who lobbied for Vignali Jr.’s release.

DEA documents surfaced in the report that portrayed Torres, Vignali Jr. and Vignali, a billboard and parking lot magnate, as part of a drug trafficking ring from the 1980s and 1990s. Vignali has never been charged with a crime. But according to recently unsealed informants’ statements, he is responsible for introducing Torres to such politicians as Hernandez and Baca, who told Pardongate investigators that he knew Torres “to be a legitimate businessman.”

Baca is not the only law enforcer Torres is alleged to have befriended. According to two sources familiar with the matter and DEA investigative reports, L.A.P.D. Sergeant Peter Torres (no confirmed relation to George Torres) ran his 2001 campaign for city council out of an office in George Torres’ swap meet. DEA reports of informant interviews also state that Sergeant Torres associated with Raul and Albert Del Real, both convicted drug traffickers with ties to George Torres.

A wiretapped conversation from December 2003 shows Raul Del Real telling his brother Albert that he saved him from getting arrested – by getting Sergeant Torres to vouch for him. In 2005, Albert Del Real told investigators he once saw his brother Raul hand money to Peter Torres at the Real Deal Carwash. Peter Torres declined to be interviewed for this story. L.A.P.D. officials said he is assigned to West Los Angeles, but is not on active duty.

EL DIABLO

In July 2007, shortly after Torres was indicted, a former Numero Uno employee contacted me and offered to describe his old boss, known to fellow workers as “El Diablo.” The employee said he worked as a butcher for four years at various Numero Uno stores from the mid- to late-’90s. He produced documentation to prove his employment and his identity, and asked that his name not be published.

During a two-hour, taped interview, he spoke candidly through an interpreter. He said he has never talked to law enforcers about George Torres.

Like the employees expected to testify at Torres’ trial, the butcher felt that Torres was tinkering with the store’s payroll – often at employee expense. “They would congratulate me on getting a raise, but then my paycheck would be the same,” said the butcher, a short man with a large head and large hands. “They’d push for more work, but the pay stayed the same.”

A 58-year-old journeyman who spent time in a Mexican jail for marijuana possession, and who since has been deported, the butcher has unsettling memories of Torres. “George, he was a real act,” the butcher said, recalling days when Torres would berate employees over the store PA system.

Yet unlike younger employees who cowered before Torres, the butcher said he displayed an irreverent streak when talking to the boss. Torres, he says, took his back talk in stride. “Not everyone saw him as a good boss. He was not like a homie. There would be 15 people ready to work, and he’d say, don’t punch in, go straight to work. Then, two hours later he’d let you punch in. I’d punch in when I arrived, no matter what he said. He’d say, ‘What’s up with you, old man?’ I’d say, ‘What’s up with you, you bastard? You’re getting rich off us.’ He’d just pat me on the back and laugh.”

For a time, the butcher lived in a house across the street from Numero Uno with a number of other employees. He described the house as a crash pad, with people coming and going amid minor drug use. Employees also hung out in a trailer next door, the butcher said. He recalls having a brush with the law and Torres insisting he take a drug test. When the butcher passed his drug test, Torres insisted he cheated and that he take another. “I said ‘You’re crazier than I am. Why don’t you get tested first and I’ll pay for them both?’”

The butcher also noticed that Raul Del Real and Nacho Meza had access to parts of Torres’ warehouse off-limits to other employees. Because the butcher could not discern any real management experience in either man – and because Del Real wasn’t an actual employee – this made him suspicious. “I thought, what’s wrong with George? He had all these kids as managers and they didn’t know anything.”

Del Real in particular, the butcher said, was too pushy and inexperienced to be taken seriously. “He was bad blood,” the butcher said. “He was cut from the same mold as George. Everybody knew what was the story there. We all did.”

One day in 1998, after police visited the market and asked Torres some questions, the butcher said to him, “Look, I know how you do your stuff. And if it’s not you, it’s your people. You cannot fool everybody.” Torres was unfazed, the butcher said, and replied, “How do you know, you

old fart?”

The disappearance of Nacho Meza is what sticks with the butcher the most. He recalled seeing Nacho return to work for the last time in October 1998. “Then two days later, people were asking about him. His mother was coming to the store asking about him. People at the store would go, ‘We haven’t seen him either.’ Nacho’s mom was crying on the street, asking if anyone had seen her son.”

The butcher said that Del Real’s reaction to the disappearance did not make sense. “Raul was so nonchalant. Come on, Nacho disappears, and Raul doesn’t say anything? They were buddies.”

Theories about Nacho’s disappearance abound. Recently unsealed documents suggest that Del Real and Meza had a falling out. Torres’ lawyers contend that Del Real, a key witness for the prosecution in the upcoming RICO trial, most likely killed Nacho.

Police affidavits identify Manuel Reynoso, the brother-in-law of Rene Cruz Reynoso, as a guy who might know something. On October 13, 2004, police put up a reward notice on the porch of Torres’ house in Downey, where Nacho used to live. Manuel Reynoso, owner of Rey & Rey Produce, was living there at the time. Within hours, according to a police affidavit, Reynoso called Torres and asked if there were problems. Torres advised Reynoso to say nothing if questioned by the police, and to never call him on the phone again. “I think it’s about that friend,” Reynoso said. Torres replied: “I think … who else?”

The butcher’s favorite theory is that an excavation at Numero Uno to make room for a new meat locker was not merely coincidental to Nacho’s disappearance. He and a colleague would talk about the concrete removal that was underway as they came to work each day. Though they have no detailed knowledge, they wonder.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Searight gets impatient with such talk. “I’ve heard all the theories,” he told me last April, declining to talk about the case in detail. “Meza was burned. He went into a meat grinder. He’s buried in cement .…”

If nothing else, the fate of Nacho Meza is a cautionary tale. Given the twisted, violent history swirling around Numero Uno in the rough barrios of South L.A., it is inevitable that, guilty or innocent, a cloud will hover over George Torres, the longtime target of failed drug investigations. Now that Searight has built an adventurous RICO case against Torres, Torres’ freedom and fortune will rest in the hands of a jury in the coming weeks.

Some might have a hard time buying it.

Not the butcher, however. “We have a saying in Mexico,” he said at the end of our interview back in 2007. “If the river is making noise, it’s because there’s water in it.”

reprinted with permission

2 thoughts on “The Suspicious LA Supermarket Mogul”